MORE OF HERB MCLEOD'S AF3

Contents:

Contact info:

Jim Michalak

118 E Randall,

Lebanon, IL 62254Send $1 for info on 20 boats.

Jim Michalak's Boat Designs

118 E Randall, Lebanon, IL 62254

A page of boat designs and essays.

(15Apr99) This issue will show some ways to guess the weight of a new design. Next issue, 1May99, will venture into the wild world of butt straps for plywood.

NEAT WEB SITE...

The YACHT RESEARCH HOMEPAGE has an interesting site that doesn't seem to fit its title. I didn't see what I would call a "yacht" at all. The site is full of small out and out speed machines that are way beyond the usual snobbish and expensive racing boats. This is where you go for backyard bomb speed with proas, hydrofoils, kites instead of sails, etc.

TEXAS MESSABOUT NOTICE...

Tim Webber is once again hosting a messabout in the Houston area on April 16, 17, and 18. For details contact Tim at tbertw@sccsi.com.

|

|

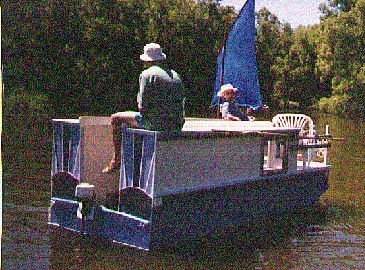

Left:

MORE OF HERB MCLEOD'S AF3 |

|

|

HISTORY...

I worked in a missile company for about 13 years and met weight engineers all the time. Looking back at the experience I might say there were three personality types of engineers. Type A was interested in power, pay, promotion and politics and not so much in hardware. Management was mostly made of Type A's. Type B guys plugged away at their work with the idea of finishing it by normal quitting time and going home - or at least looking busy until quitting time. And Type C's were the new guys, right out of college and still full of enthusiasm and patriotism. It usually took about five years for a C to evolve into an A or B. Advance design, where the real weight guessing was done, was usually full of Type A's managing some Type C's. But when a program starting getting hot some Type B's might be brought in to do some reliable work. Then managers ran the risk of the Type B reminding everyone that the Advanced Design Group had never won a program or made any actual flying hardware in the 20 years of the group's existance. (The missiles being assembled out in the shop were designed by other companies.) And the Type B's might point out that the calculations, which had been done by the Type A's and C's, upon which the program's future was based, were hopeless.

ENTER MISSILE BALONEY...

And it came to pass that I, still a young type C at the time, was teamed up with Harry, a type B weights engineer, on an "advanced cruise missile" program. I was a strength engineer at the time but was quite curious of how the weights guys did their work. Given a half dozen concept missiles at a Monday meeting, Harry would produce detailed weights for each say by Thursday. I was wowwed!

One day Harry showed me how it was really done. He had secreted in an obscure book a graph he had made that plotted the weight vs the volume of existing missiles, the source of the info being Jane's All The World's Whatever. The data points formed a straight line on his graph. That meant that in spite of variations in size and shape, they all had the same density! So Harry's work was simply to figure the volume of the proposed missile and multiply that by that universal density and, Voila!, you have an accurate weight of the proposed missile. Doing that did not take four days, of course. It might be done in a few minutes in the privacy of the potty and the other days spent looking busy.

The reason the missile chart worked so well, Harry said, was that missiles are always jammed totally full of stuff. There was no empty volume to upset the average density calculation. The average density might change a bit with history as new technology made for denser packaging, for example when the guys in the shop found they could install oversized wire bundles into the fuselage by pounding them in with hammers.

And Harry assured me the current average density of missile was the same as that of baloney, similar to that of water. He called it "missile baloney" and you could get the correct weight of a new proposed design by imagining it to be a giant baloney sausage and that was all there was to it. So if your missile was say 20" in diameter and 20' long it would have about 43 cubic feet of missile and it would weigh about 2600 pounds fueled up and ready to go. Of couse you would not report to the Type A's that the weight was "about 2600 pounds". You would say something like 2624.6 pounds or 2587.2 pounds. If you knew the head Type A had a pet concept you would make that one be the lightest.

Harry assured me that any further work would simply be to find out how that weight was distributed among the missile's elements because the baloney had "local lumpiness". But the total could never vary far from the first guess.

I was of course sworn to secrecy about the method. But one day a young Type C engineer tried to impress the Type A's by writing up a memo of the one line missile weight graph and presenting it as his own. They fired him! No kidding.

Harry went to work on his "Grand Unified Baloney Theory Of The Universe".

ENTER BOAT BALONEY...

When I started drawing boats about 10 years ago I saw a need to estimate the weight of new designs using typical plywood construction and wondered if there might be such a thing as "boat baloney"? I came up with the following chart:

I'm afraid the method does not work so well with boats because boats aren't usually jammed full of stuff - there is lots of empty volume. And because boat hulls are built in entirely different ways by different people, even when they use the same set of plans. To illustrate that I'll recall the time I took my old Gloucester Gull dory, the Payson/Bolger boat, out rowing with Dan Knodler who also has a version of the same design. Mine was made of 1/4" plywood with taped seams and totally stripped out. It weighed 65 pounds. Dan's was built by a pro from 1/2" plywood with hardwood seats and gingerbread and weighed about 150 pounds. I think Payson said one built right to the plans as he made them weighed about 100 pounds.

Looking at the above chart it seems that empty hull baloney has a density of about 1.5 pounds per cubic foot if lightly constructed to about 3 pounds per cubic foot if heavily constructed. Remember this is just for empty plywood hull structural weight. I would say "lightly constructed" would mean a simple undecked boat like a canoe or rowboat that borders on flimsy. "Heavily constructed" would mean a more complex decked hull with some beef to it. Actually you could make a case that heavy could be heavier than I am showing.

Let's use this issue's feature boat, the shanty boat Shanteuse, as an example of using the chart. This boat is a constant 6' width, 15' long, with a housing box that is 10' long and 4' high. It's total volume is about 300 cubic feet. If we use an average boat baloney denisity of 2.25 pounds per cubic foot as suggested by the chart we would expect the empty hull to weigh about 675 pounds. Not much to figuring that!

The above just estimates the structural weight of the hull, not the ballast, sail rig or motor, etc...

ENTER THE CREW WITH ITS JUNK...

Usually one might figure the weight of the average adult as 175 pounds. But I know some of you weigh twice that and some weigh half that. It's very important with small boats in particular to get a good estimate of the proposed crew weight and be honest with yourself about how many boating friends you have and how often they will really be boating with you.

As for personal gear, food, and water, Dave Gerr recommends about 20 pounds per person per day. Sounds reasonable. For living aboard he says 400 to 1000 pounds of junk per person.

Small outboard motors with a bit of fuel seem to weigh about 50 pounds although it can vary quite a bit. Usually an available motor is easy to weigh on a bathroom scale.

If you want ballast, the old rule for ballast is about 50% of the empty hull weight although its placement is very important. Nowadays one can check the ballast requirements a lot easier than in the olden days because computers are great for this sort of figuring.

Sail rigs don't actually weigh very much. As we saw last issue a 24' mast about the size of a Micro or Birdwatcher mast weighs about 30 pounds. And that is about the most mast a man can step by himself without special gear. The sticks used for booms are easily estimated and modern sailcloth is really quite light, a 100 square foot sail weighing maybe 4 pounds. Leeboards and centerboards can be quite large and heavy.

Add up all the bits and you will have an estimate of the total floating weight of the boat. Then you can get serious about making sure your proposed hull will float it properly by using the methods shown in the last issue.

ENTER THE PLYWOOD PANEL LAYOUT...

And it came to pass that Payson spoke unto Bolger saying, "Go forth and bring unto my people drawings of plywood sheets with the boat parts laid upon that they might be knowing of how much to buy and be not wasteful."

Payson and Bolger didn't invent the plywood panel layout but they popularized it and made it a key element of instant boats. All the plywood parts of the boat are laid out in scale on standard 4' x 8' sheets of plywood on a drawing. The layout is supposed to be a guide to the economical use of the plywood. It doesn't adapt too well to the traditional cut-to-fit style of building. I see in a recent Boatbuilder magazine where Thomas Firth Jones built a Payson/Bolger catboat by traditional methods instead of the taped seam instant method shown on the drawings. He kidded Bolger and company about spending the time to lay out all the parts. But the layout is an important material and labor saver to someone building instant style.

Once you lay out all the parts you can determine how much plywood you will be using. And if you know how much plywood you are using, you know how much the pile of plywood weighs. And since an instant boat is mostly plywood, you get an excellent idea of how much the hull and plywood parts will weigh. Then you can update your idea about the density of boat baloney.

Here is the plywood panel layout for my design Mixer. All the hull parts including the leeboard, and rudder parts are there on four sheets of 1/4" plywood:

Wood density varies quite a bit. But a 1/4" sheet of plywood usually weighs about 25 pounds, a 3/8" sheet about 37 pounds, and a 1/2' sheet about 50 pounds.

"But," you say, "there is more wood in the boat than just the plywood. There is the framing wood too." That is true. But then again not all the plywood gets used. Here is a general rule that I use with plywood boats with nail and glue joints that require stick framing and conventional chine logs - allow about 30 pounds per sheet of 1/4" plywood, 45 pounds per sheet of 3/8' plywood, 60 pounds per sheet of 1/2" plywood, etc. Taped seamed boats are lighter than framed boats and can indeed be estimated fairly well using just the weights of the plywood sheets. I think about the only warning I might give when using this method of estimating the weight of a new design is that often the ply panel layout also contains temporary forms that won't be permanently in the hull. Those areas should be excluded from the total. So when I look at the plywood panel layout of Mixer shown above, I think instantly, "No more than 100 pounds in four sheets of 1/4" plywood and taped seams. In fact with the sail rig and hatches stripped off for cartopping it might be around 80 pounds." I don't remember if David Boston who built the first one weighed her.

By the way encapsulating a boat like Mixer will increase its weight. The numbers I mention above would include minimal paint but not epoxy coating. So you might add maybe 10 pounds per gallon used.

Now let's use Shanteuse as an example of getting a close weight estimate of hull weight by using the ply panel layout. When I lay out all of Shanteuse's parts I found it needed eight sheets of 1/4" plywood and six sheets of 1/2" plywood. So a guess at the hull weight, more refined than the baloney weight, would be eight times 30 pounds for the 1/4" sheets and six time 60 for the 1/2" sheets. That totals 600 pounds. When I wrote up the catalog blurb below for Shanteuse I said 700 pounds thinking she has more than the ordinary amount of framing. But I could be wrong. Until someone builds one to plans and weighs it, we won't know.

NEXT TIME...

I'll show ways to join plywood panels together.

SHANTEUSE

SHANTEUSE, SHANTYBOAT, 16' X 6', 700 POUNDS EMPTY

Shanteuse is a slight enlargment of the mini shanty Harmonica. Shanteuse is 1' wider than Harmonica and has a 3' extension on the stern to allow a small back porch and a motor mount that is totally out of the living area.

Here is a photo of the original Harmonica:

I've also made Shanteuse a little heftier. I'm thinking this one will weigh about 700 pounds empty where Harmonica comes in at around 400 pounds. I'm not sure if the extra beef is needed because Harmonica seemed totally adequate to me as far as strenght and stiffness go. But the extra size of Shanteuse is probably going to take it out of the compact car tow class. The plywood bill for Shanteuse looks like six sheets of 1/2" plywood and eight sheets of 1/4" plywood. I would not use fancy materials on a boat like this and am reminded of Phil Bolger's warning to never spend a lot of money building a design that was intended to look cheap. I see pine exterior plywood at my local lumberyard selling for $11 or a 3/8" sheet and this entire boat could be built of it. So the plywood bill would be less than $200 and I'm thinking the entire bill less than $500. The pine plywood looks quite good to me, its main drawback being that it doesn't lay very flat.

These boats can be very comfortable to camp in. The interior volume and shape are not unlike the typical pickup camper or the volume in a full sized van. It's not huge, it's cozy. The top has an open slot 28" wide from front to back on centerline. You can close it over with a simple tarp, leave it open in good weather, or rig up a full headroom tarp that covers the entire boat. I've shown lots of windows but the window treatment can be anything you like. Chris used very small windows on the original Harmonica and I thought it quite nice. You do need to see out. I would be tempted to cover the openings with screen and use clear vynal covers in the rain or cold. For hard windows I think the best material might be the Lucite storm window replacements sold at the lumberyard. Easily worked, strong, and not expensive.

As for operation, these are smooth water boats. So it is best to stay on small waters that never get too rough. On bigger waters you need to watch the weather very carefully. For power I would stick to 5 or 10 hp but I'm very much a chicken about these things.

Plans for Shanteuse are $20 until one is built and tested.

Prototype News

Some of you may know that in addition to the one buck catalog which now contains 20 "done" boats, I offer another catalog of 20 unbuilt prototypes. The buck catalog has on its last page a list and brief description of the boats currently in the Catalog of Prototypes. That catalog also contains some articles that I wrote for Messing About In Boats and Boatbuilder magazines. The Catalog of Prototypes costs $3. The both together amount to 50 pages for $4, an offer you may have seen in Woodenboat ads. (If you order a catalog from an internet page you might state that in your letter so I can get an idea of how effective this medium is.) Payment must be in US funds. The banks here won't accept anything else. (I've got a little stash of foreign currency that I can admire but not spend.) I'm way too small for credit cards.

Usually when a design from the Catalog of Prototypes starts getting built and is close to launch I pull it from the catalog and replace it with another prototype. So that boat often goes into limbo until the builder finishes and sends a test report and a photo.

Here are the prototypes abuilding that I know of:

IMB: I heard recently from the Texas IMB builder who said, "I want to let you know that IMB is alive and looking good. She is now right side up and sitting on her cradle. Soon this boat and carrier will be mounted on the small trailer I have ready......" Then I got this photo from Roger Harlow by way of Tim Webber.

Fatcat2: There is an old timer (80 years +) in Minnesota who has completed the hull of a Fatcat2. Fatcat2 is a simple 15' x 6' catboat, gaff rigged and multichined. The sail rig is nearly done now.

Mixer2: Mixer2 is more or less the original Mixer with a rough water bow like Toto's. 12' x 3'9" and about 90 pounds. Has a sail rig. I got a call from a Colorado builder who wanter to learn to sail and apparently has the boat well along. He also built last year a Smoar which is a 12' version of Roar2 and was very satisfied with it. As I talked with him on the phone I got down on my knees and begged for photos.

Frolic2: I recently heard of two of these going together. One is in Colorado and seems to be on the back burner for now. The other is in Oregon and is on the front burner. He started it in January and is about half done, hoping for an early summer launch.

RB42: This is an 18' rowboat meant for two. It's never been in any of my catalogs but the Canadian builder has it well underway. It is essentially a reworking of Toto to longer and wider but not much deeper.