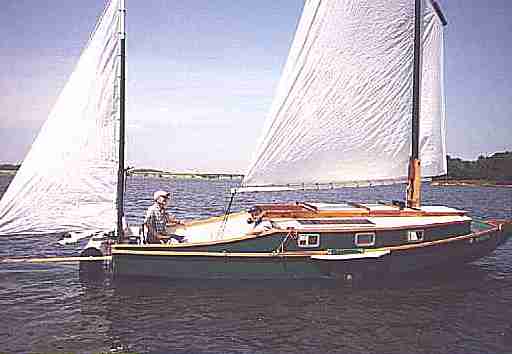

Richard Spelling and son about to hit the beach in AF2 at the Midwest Messabout.

Contents:

Contact info:

Jim Michalak

118 E Randall,

Lebanon, IL 62254Send $1 for info on 20 boats.

Jim Michalak's Boat Designs

118 E Randall, Lebanon, IL 62254

A page of boat designs and essays.

(1jul01) This issue talks about another type of wooden boat construction, the "instant" construction. Next issue, 15jul01, will review the essay on making a weighted rudder for your small sailboat.

|

|

Left:

Richard Spelling and son about to hit the beach in AF2 at the Midwest Messabout.

|

|

|

WOODEN BOAT CONSTRUCTION 2

WOOD2...

ENTER THE FLAT IRON SKIFF....

All of the techinques discussed earlier for building wooden boats relied on a skeleton or form of the boat around which the parts of the boat were fitted and assembled. Usually in small boats the forms are set up on a ladder like base, the forms spaced every 2 or 3 feet mounted perpendicular to the base and very carefully leveled and aligned. The stem and stern and keel pieces are also carefully made and notched and rabbited, etc, and attached to the base with precise alignment before the planking goes on. The smaller boats are usually built upside down. Larger boats were usually made right side up starting with the keel and everything else carefully erected on top of it (although I think the Herreshoffs always built their boats upside down). The base and forms need to be rock solid and once you start the project it is very hard to relocate it. For some boats the lumber in the base and forms will exceed the lumber that actually ends up in the hull. If the boat is to be massed produced the form can be used over and over again.

Now imagine that you are building just one boat - very common for amateurs. And imagine that you have no place to build where you can place a form immovable for months as you work in your spare time. Or imagine that you have no surface that will easily accept a form that should be immovable, that is that you have a concrete floor and you don't want to set anchor bolts into it.

Those problems were solved long ago with what is often called the "Flat Iron Skiff". I know that flat iron skiffs were common 100 years ago, but I doubt if they go back much beyond 200 years because they require cheap wide flat boards and good nails.

The concept behind the flat iron skiff is totally the opposite of the last issue's methods. In all of the previous methods the planking is fitted to take the shape of the hull. In a flat iron skiff the planks are shaped first and the hull takes a shape determined by the planks. In the past flat iron skiffs could be either ugly and crude if the builder had no experience, or pretty and refined if the builder had polished his ideas with several boats or was very lucky with the first ones. Also in the old days the flat iron skiff was indeed shaped like a flat iron - pointy bow, squared stern, and a wide flat bottom.

A flat iron skiff isn't built around a solid form. Instead the side planks are first cut to shape and bent around bulkheads or frames or forms which may or may not be temporary. All of these elements are defined in the plans so there should be little or no trial and error fitting. Once these basic elements have been assembled the boat's shape has been totally defined although the rest of the boat such as the bottom or decks will need proper fitting. The assembly need not be built on a rock solid base provided care is taken to see that it is straight and untwisted at every stage of construction. Usually boats like this are built over simple saw horses as you see in most of these photos, but the first photo shows the kids making a flat iron dinghy on top of a picnic table. Larger ones are often built propped a few inches off the floor. Often nothing need be leveled. Usually the best way to maintain alignment is with a string or straight edge to keep the centerlines of the forms all in a row, thus keeping the hull straight, and by eyeballing to see that the tops of the forms are all parallel, thus keeping the hull untwisted.

Howard Chapelle in his great book "Boatbuilding" gives the flat iron skiff a single page's essay, actually one long paragraph. In a book over 600 pages long, you can feel what he thought of the method in 1941. He says,"It is obvious, then, that this method is not suited for amateur buildng, except in the roughest and most hurried construction." But then he finished that paragraph with a comment that became the future, "It should be added, however, that in some cases it is possible to build from a design by this method, if the shape of the sections permits the expansion of the side planks or if a half - model is made by which the sides may be expanded to scale."

I don't know if Chapelle lived to see the development of "instant" boats by Payson and Bolger. They went public with the method by the 1970's although others like William Jackson had used the method in popular magazines much earlier. Instant boats are flat iron skiffs with more modern materials, in particular with lumberyard plywood. And perhaps World War 2 had its effects here too, both in making the materials more common and also in making the drafting techniques needed to expand the panels more common. After all, big ships were mass produced and not by the cut and fit methods of the 1800's.

So in a way there was a total change in homebuilt boats in a 30 year span. In the messabouts we have had here in the midwest over he past ten years there have been very few conventionally built boats although those that are made so are often works of art.

One might argue that traditional methods produce better boats because they allow a lot more variations in hull shaping. True. But the flat iron "instant" method is catching up rapidly for two reasons. One is that new materials continue to appear that allow the builder even more latitude in shaping. The obvious thought here is the use of taped seams to replace the bevels, which can be tricky in some situations, in even flat iron construction. And also the invention of computers and programs that can expand desired hull shapes in an instant to a degree of accuaracy that boggles the mind. Indeed, one could even survey the lines of a lapstrake boat like a Viking boat, punch the offsets into a computer program, and have it direct a machine to cut out every plank in the hull in gigantic sheets of plywood and make a brand new Viking boat. But you see how technology can also change boatbuilding from an art into tedium. I'm reminded of my first year at the missile company in 1975 at a time when computers were replacing hand calculations and all the judgements that went with them. As I poured over the latest printouts with Ron who had started before computers, he commented, "We're not engineers anymore. The computer has turned us into book keepers."

(As an aside I will mention that one technique to expand the shapes of panels making up the boat hull was presented in the late 1950's by Sam Rabl who was, I think, a contemporary of Howard Chapelle. The Rabl essay was reprinted in Boatbuilding Magazine about 10 years ago and I'm thinking it was something presented by Dave Carnell who has been boating a long time and never throws anything away. Rabl wrote before the days of today's computers and did all his expansions by mechanical drawing. I tried the Rabl method and found it unreliable when done in the typical drafting scale, as did Phil Bolger who is much more meticulous at drafting than I am. But after a long long look at Rabl's work I found I could reduce it to some equations that even an Apple2 could solve in a flash to many decimal places. Two common programs that you can get that I think use the Rabl technique are Ray Clark's Plyboats and Greg Carlson's free Hulls program.)

(As a second aside I'll say that even a flat iron skiff can be built over a solid mold or frame, as a builder in production might do. So the builder has his form and given enough boats to build will make patterns of the pieces so they can be mass produced too and assembled on that solid form. Harold Payson did that for a long time with his Bolger designed dories. He surveyed his patterns and presented them in one of his books. And those are what I used to make my old dory without a solid mold, just by wrapping the sides around the sections shapes as in a flat iron skiff.)

So modern techniques have ended the worries that Chapelle had about building a boat in the flat iron style. I would think that today any shape that can be done in plywood can be prefabricated to shapes figured on the drawing board and built without a solid building form. What started with flat iron skiffs now includes prams, dories, flat bottoms, v bottoms, and multichines so numerous that the end result is a round bottomed boat! Of course, the expansions can get tedious even by computer and a fellow might eventually reach a point where he says, "Hey, this would have been easier building over a form like Chapelle did." And if the complexity gets really great the boat becomes a jigsaw puzzle instead of a painting.

NEXT TIME...

I'll repeat the essay about making a weighted rudder for your small sailboat.

PIRAGUA

PIRAGUA, SWAMPBOAT, 13' X 30", 70 POUNDS EMPTY

The photo above is of a Piragua built by Bob Taylor down in Texas. Piragua is a very simple useful boat. I probably get more Piragua photos than of any other boat, an indication that more Piraguas get built. Piragua is made from two sheets of 1/4" plywood with very simple old fashioned glue and nail construction. It's very suitable as a first project, both as a way to learn construction and as a boat you will use a lot. But the first Piragua almost never got built, an indication that you can't tell what will be popular in this hobby. I drew it up and thought it pretty good for what it was supposed to be. I put it in my prototypes catalog and had two blueprint sets printed. After a year in the catalog I still had those two prints! I took it out of the catalog. About a month later I sold one set to Don O'Hearn and gave the other set away to Brian Waters who had ordered other plans, saying he was looking for a project for his sixth grade shop class.

Both boats got built! Waters' bunch of kids finished the first one, shown below. Brian also sent an article from his local newspaper showing the boat with himself and a class full of smiling kids behind the boat. I still have the copy on my wall and always thought it to be a trophy!

O'Hearn's boat followed very closely and he lives close enough that he brought the boat to our Messabout and I had a chance to try it myself. I thought it was quite good. I could just barely stand up in it, very common of this sort of narrow boat. It's 24" wide on the bottom and I've found that you can't reliably stand up in something that narrow. Don used the boat for fishing in little waters and keeps his butt on the seat. You paddle Piragua with a double paddle like a kayak. Here is Don's boat with his son at the paddle.

Here is another boat local to me by Rich and Ben Scobbie of St. Jacob, Illinois.

Steve Jacob built this one with Spanish moss hanging above. His used taped seams instead of the external chine logs with some crown to the decks.

And here is a photo from New South Wales from Ashley Cook. I'm very glad these boats are getting around. You can see these are best as solo boats but have the room and capacity to take some passengers in good conditions. Also you can tell that kids really take well to this sort of boat. They are easily understood in one glance. Still, you have to take any boat seriously. If you fall out of or capsize a boat like this you well need special training and gear to get going again in deep water. If built with the end air boxes the boat will have plenty of buoyancy but probably won't be stable enough for you to get back in. I think the only way to do the job is with a bailing scoop and a way to lash the paddle across the boat with a flotation cushion attached to one end to stabilize the boat in roll. You have to do all this as you swim around. My own appoach is to use these close to shore in warm water!

Plans for Piragua are still $15.

Prototype News

Some of you may know that in addition to the one buck catalog which now contains 20 "done" boats, I offer another catalog of 20 unbuilt prototypes. The buck catalog has on its last page a list and brief description of the boats currently in the Catalog of Prototypes. That catalog also contains some articles that I wrote for Messing About In Boats and Boatbuilder magazines. The Catalog of Prototypes costs $3. The both together amount to 50 pages for $4, an offer you may have seen in Woodenboat ads. Payment must be in US funds. The banks here won't accept anything else. (I've got a little stash of foreign currency that I can admire but not spend.) I'm way too small for credit cards.

Caprice: Chuck Leinweber of Duckworks Magazine has finished the prototype Caprice. I got a ride and some photos at the Midwest Messabout and will have a full report soon.

Normsboat: This is an 18' sharpie being built by Cullison Smallcraft in Maryland. You should be able to check on it by clicking through to his web site at Cullison SmallCraft (archived copy, actual site no longer active). He is presenting an excellent photo essay of how to assemble a flattie. This boat has been launched and I'm waiting for photos and a test report.

Vamp: I received word that a prototype of the little rowboat Vamp is completed up in Utah. Hopefully photos and test report soon.

Family Skiff: A Family Skiff has been started in Virginia.

HC Skiff: One of these is going together in Massachusetts.

Electron: An Electron has been started in California.

AN INDEX OF PAST ISSUES

Herb builds AF3 (archived copy)

Hullforms Download (archived copy)

Plyboats Demo Download (archived copy)