Brian Walker's delux Roar2 with sliding seat, daughter, dog, cat.

Contents:

Contact info:

Jim Michalak

118 E Randall,

Lebanon, IL 62254Send $1 for info on 20 boats.

Jim Michalak's Boat Designs

118 E Randall, Lebanon, IL 62254

A page of boat designs and essays.

(1Nov03) This issue will rerun the oarmaking essay. The 15Nov issue will talk about glassing plywood.

THE BOOK IS OUT!

BOATBUILDING FOR BEGINNERS (AND BEYOND)

is out now, written by me and edited by Garth Battista of Breakaway Books. You might find it at your bookstore. If not check it out at the....ON LINE CATALOG OF MY PLANS...

...which can now be found at Duckworks Magazine. You order with a shopping cart set up and pay with credit cards or by Paypal. Then Duckworks sends me an email about the order and then I send the plans right from me to you.

|

Left:

Brian Walker's delux Roar2 with sliding seat, daughter, dog, cat.

|

|

|

Making Oars

I decided to rerun these rowing articles that first appeared here in the winter of 98-99. I've left out some of the details that appeared in those issues and added other details.

MAKING A SET OF OARS....

I'm going to show drawings for 7' oars which are about the most useful length for me.

WHAT KIND OF OARS....

The oars I make are really derived from the patterns of the late Pete Culler. They are characterized by having heavy square looms inboard of the locks and long narrow blades in the water. An example is shown in Figure 1.

The square looms are easy to build, help balance the oar, help locate the oar in the locks, and keep the oar from rolling around on the wales.

The long narrow blades go against modern thinking of spoons, but for long distance rowing, long and narrow is the way to go. The average mortal can only pull so much of a load, in spite of what an Olympian might do. The Culler blades can match the mortal's pull. They might slip a bit when starting a heavy boat from a standstill, but once up to speed, the have full grip on the water. They balance better. They are less fatiguing. They have less windage. By the way, the oars of traditional Irish caurrahs have no blades on their oars. Neither do the paddles of some traditional kayaks.

WHAT YOU NEED...

Oars are made from four materials - wood, glue, leathers and varnish.

For wood, I use 1x6 pine boards. The pattern shown in Figure 1 will just barely make an oar from a 1x6. I try to buy a single board long enough to get out both oars. For example, for a pair of 7 foot oars, I buy a board 14 feet long if I can. That way the oars will be a close match on weight, stiffness, and color I like to use soft wood like pine, It is easy to work and makes a light oar. It need not be clear wood although clear is easier to work Small solid knots are fine and look good too. I've never worried too much about grain because the sticks get laminated and tend to stay straight. But the straighter the grain the better.

For glue I prefer plastic resin "Weldwood" glue and doubt if there is anything better for making oars. Pour some in a cup and squirt in cold water until it has the consistency of normal woodworking glue like "Elmer's. I've found it to quite true that this glue will not set properly until it is a t 70 degrees F for twelve hours like it says on the can. But don't hesitate to use epoxy if you already have it on hand.

For leathers I don't use leather. I bind the 8 inches just below the square section of the loom with synthetic mason's twine, about 3/32" diameter. It lasts for years.

For varnish I use ordinary oil based spar varnish.

Now let's talk tools. The tool I use the most in making oars is a bandsaw and I hate to say that because it's not a cheap or small thing that everyone will have. The problem is that you've got to saw a 2-1/4" thick blank. Hand saws will work and the effort should get you in shape for rowing. After all, oars were invented long before the bandsaw. But I see Dave Carnell has built oars using his table saw and others have built oars with a sabersaw.

HOW TO BUILD...

First cut the 1x6 boards to the proper length. lay out the centerline with a straight edge. Then draw the pattern for the center piece, the one with the blade, around the centerline. Cut out the center lamination following the line closely with your saw, because the outer laminations of the blank are made from the off fall and there isn't much extra.

You can draw patterns of the outer pieces and cut them out. But it's easier to glue the pieces directly to the center piece and trim them after the glue cures. Trial fit the outer pieces. You may have to trim them for the proper shape where they blend into the blade area of the centerpiece. When you are satisfied, butter them up well with glue, and clamp them in place. You may need to tap in a a light temporary nail to keep the pieces from sliding around on each other because almost all glues are quite slippery until they start to set. Try to get glue squeezed out all around. And be sure the blank is resting straight while curing. Walk away from the blanks until the glue has cured hard.

After cure, trim the outer pieces to match the centerpiece. Use a plane and sander to work these pieces to their final lines, being careful that these faces remain square to the other two unworked faces.

Now cut the two unworked faces of the handle and loom of the oars to their final dimensions. Draw centerlines down the two worked faces and lay out the shape of the handle and loom. Cut to the lines and sand smooth. At this point the cross section of the oar from handle to loom is square.

The oar drawing shows how much of the loom is left square. The rest is to rounded. You start by drawing lines on handle and loom that allow you to make the cross sections octagonal. You can draw them using the gadget shown in Figure 2. Then cut down to the lines with a half round rasp where the lines blend to the square section of the loom. Then use a drawknife or plane to remove the rest of the material down to the lines along the shaft. Now she's eight sided. To round it you're supposed to sixteen side it and then round it out. To tell you the truth, I leave mine eight sided, including the handle and the area which fits in the rowlock.

Lastly you need to trim mass out of the blade. I plane the blade down so its edges are 1/4" thick. Then I use the front roller of my belt sander to hollow the blade slightly on either side of the center, leaving a ridge in the center.

I think the only critical part of these oars strength wise is the 1-1/4" section where the blade meets the loom.

Give the oars a good overall sanding, but leave the handles rough.

Wrap the rowlock area, from the square section down 8 inches toward the blade, with mason's twine. Wrap it tightly and use knots to secure it.

Give the oars three coats of spar varnish. That includes putting varnish on the twine binding. It will go a long way towards holding the binding in place. Don't varnish the handles.

An easy and effective "button" can be made be added to the bound area, to provide a stop which will locate the oar lengthwise in the lock, by wrapping it tightly with three wraps of 1/4" shock cord, and tying the cord with a square knot. If the tension in the cord is right, it will stay firmly in place while rowing and yet allow repositioning up and down the bound area to change rowing leverage when required.

A ROWING SEAT/DITTY BOX....

Figure 3 shows a rowing seat/ditty box that I've been using for years. You might have to tinker with it a bit to get it to fit your butt. As for the height of the box, it is nice for a bar placed across the rowlocks of your boat to cross you at belly button height. That would include any padding on the seat such as a flotation cushion which you should have on board anyway. For that matter a stack of two or three stiff flotation cushions can make a pretty good rowing seat.

Here is what the seat looks like for real, this one about 15 years old now. Here are some things you might keep inside the seat: spare oarlocks, a knife, some line, sunscreen, Vasoline, binoculars, compass, whistle, and some energy bars. Always take a lot of drinking water with you also when you go rowing.

OARLOCK SOCKETS...

If your hull's side have limited flare, say less than 15 degrees, you can make some cheap oarlock sockets that are as good as store bought. I got the idea for these, plus the oarlocks that follow, from Phil Bolger who used them on his Spur 2 rowing boat that appears in his book BOATS WITH AN OPEN MIND.

Here is how it's done.

What we have here is simply two metal plates bolted to the wale with the proper sized hole (usually 1/2") drilled in each. Phil had his made of stainless steel. I made mine out of aluminum and have had no problems. I used an aluminum yardstick of the type carried by lumberyards for use with drywall as the basic material. I think the metal is about 1/10" thick and about 1-1/8" wide. I cut the aluminum to 3" lengths, stacked them up and drilled the oarlock hole and the bolt holes all at the same time. Filed off any sharp edges. Clamped the plates in the proper position and drilled the wooden wale. Bolted the plates in position and that's it. These work well because the oarlock bears on the metal parts which are about 1" apart, a bit more than the usual shallow factory sockets. So far I haven't worn them out. By the way, it helps to grease any oarlock from time to time, ordinary Vasoline works well.

BOLGER OARLOCKS...

I haven't tried these but Phil swears by them. It is really a thole pin with a bracket to retain the oar. Phil has always said that thole pins are better than the usual factory oarlock where the oar centers directly over the rotating pin. With a traditional fixed thole pin the oar rotates around the fixed pin as it bears against it and Phil says that is a better motion than with the factory oarlocks. The pin shown here could also be fixed, the bracket rotating around the pin with the oar! I should try these.

NEXT TIME...

...a talk about glassing plywood.

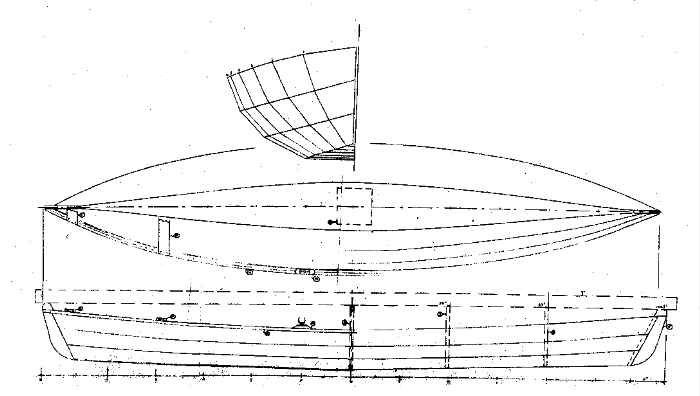

LHF17

FAST ROWBOAT, 17' X 3.5', 100 POUNDS EMPTY

Don't remember where I read this but 100 years ago rowing was all the rage, the sort of thing you did on for fun. They said its popularity dropped and died after the invention of the modern "safety" bicycle which replaced it for athletic recreation. The Herreshoffs in Rhode Island had a historic boat business going at that time making everything from huge racing yachts to dinks to torpedo boats. L. Francis Herreshoff carried on the tradition in the 1900's being a great designer, artist and writer and educator. I suspect anything he wrote is worth seeking out. I have a copy of his book SENSIBLE CRUISING DESIGNS which I think is a compilation of articles he wrote for THE RUDDER magazine about 50 years ago. Lots of really good stuff in there. Among it is a discussion of good rowing boats with a "cartoon" presentation of a 17' rowing boat that would be fast and able but also simple and comfortable and not extreme. John Gardiner, another legend in small boats whose writings you should seek out, elaborated on that LFH cartoon and presented offsets for his idea of that boat in his BUILDING SMALL CLASSIC CRAFT, VOLUME 2. Both L. Francis and Gardner were used to traditional lapstake construction and thought nothing of presenting such a design. But the special lumber and tools needed for lapstrake are not common at least where I live. So I got an order for the LFH design redone for taped seam plywood. Thus the design I call the LFH17. As with L. Francis' original the LHF17 has a narrow flat bottom making it a dory of sorts and is identical bow and stern.

This boat will be a bit more complicated to build that most "instant" boats, I'm quite sure. For one thing it has three panels on each side to keep track of. And since they are long narrow pieces, all with a lot of flare, I doubt that it will jig itself like boats with wide plumb sides. So even though I show the expanded shapes of the individual planks I've also shown it made on a backbone or ladder frame so that it can be kept in proper alignment as it goes together. And, as with the original which probably had six or so strakes to each side instead of the three I show, the bottom bilge panel or garboard twists about fifty degrees in its journey from mid boat to stem and I would expect a fair amount of pushing and shoving required.

LFH17 needs four sheets of 1/4" plywood with taped seam construction.

Plans for LFH17 are $20 until one is built and tested.

Prototype News

Some of you may know that in addition to the one buck catalog which now contains 20 "done" boats, I offer another catalog of 20 unbuilt prototypes. The buck catalog has on its last page a list and brief description of the boats currently in the Catalog of Prototypes. That catalog also contains some articles that I wrote for Messing About In Boats and Boatbuilder magazines. The Catalog of Prototypes costs $3. The both together amount to 50 pages for $4, an offer you may have seen in Woodenboat ads. Payment must be in US funds. The banks here won't accept anything else. (I've got a little stash of foreign currency that I can admire but not spend.) I'm way too small for credit cards.

Here are the prototypes abuilding that I know of:

The Texas Ladybug uses up all the man's clamps:

The Tennessee Shanteuse is rightside up now on a trailer:

Out West a young fellow poses with his Picara project:

AN INDEX OF PAST ISSUES

Hullforms Download (archived copy)

Plyboats Demo Download (archived copy)

Brokeboats (archived copy)

Brian builds Roar2 (archived copy)

Herb builds AF3 (archived copy)

Herb builds RB42 (archived copy)