Gary Blankenship and Noel Davis about to launch at the start of this year's Everglades Challenge.

Contents:

Contact info:

Jim Michalak

118 E Randall,

Lebanon, IL 62254Send $1 for info on 20 boats.

Jim Michalak's Boat Designs

118 E Randall, Lebanon, IL 62254

A page of boat designs and essays.

(1apr07) This issue will present Gary Blankenship's report on sailing the Everglades Challenge 2007. The 15 April issue will probably rerun an old rowing essay.

MESSABOUT NOTICE:

THE REND LAKE MESSABOUT WILL TAKE PLACE ON JUNE 8 and 9 AT THE GUN CREEK RECREATION AREA AT REND LAKE IN SOUTHERN ILLINOIS. MORE DETAILS WILL FOLLOW BUT IT MIGHT BE PRUDENT TO MAKE CAMPING RESERVATIONS IF YOU INTEND TO ATTEND.THE BOOK IS OUT!

BOATBUILDING FOR BEGINNERS (AND BEYOND)

is out now, written by me and edited by Garth Battista of Breakaway Books. You might find it at your bookstore. If not check it out at the....ON LINE CATALOG OF MY PLANS...

...which can now be found at Duckworks Magazine. You order with a shopping cart set up and pay with credit cards or by Paypal. Then Duckworks sends me an email about the order and then I send the plans right from me to you.

Everglades Challenge 2007

TO RECAP....

Gary Blankenship and Noel Davis sailed and rowed Gary's Frolic2 in the rough and tumble 2007 episode of the Everglades Challenge race. They finished 4th overall! Gary wrote up a great report and I decided to run the whole thing in one issue. After Gary's report I will present a bit by Chuck Leinweber who crewed with Gary last year and sailed in a different boat in this year's race. Then I will close with a few words. Here goes...

"....OKAY, you asked for it :-). If you have any specific questions, please ask. I'm still a bit overwhelmed by the whole experience and I'm always thinking of things I left out. Like how the downhaul was adjusted everyday depending on the conditions expected -- it was moved aft if it was an off-the-wind day, which reduced weather helm, and forward if it was expected to be a windward day, which counteracted the lee helm I sometimes encounter. You can see in Matt's pics that I goofed the first day and had the downhaul forward in what proved to be an offwind day . . .

Gary

AND NOW THE STORY BEGINS...

"It was dead low tide and there were 20 yards of mud stretched between Oaracle and the beach at Chokoloskee Island, three miles south of Everglades City, Florida. Noel and I were only a few steps off Oaracle and we were in trouble. The mud was black, smelly, sticky, and soft. We were sinking to almost the tops of our boots as we struggled ashore.

Disaster hit Noel first. He had spent five hours carefully drying his right hand sailing glove, Now he lost his balance and pitched forward, burying his begloved hand past the wrist. Worse, he couldn't extricate himself except by plunging his left hand into the ooze for balance. Struggling upright, he wavered for a moment, then lost his balance again and sat down heavily in the muck. After a worrisome moment, Noel roared - with laughter. I knew I had the right crew.

My fate wasn't much better. Struggling only a couple steps further, I pitched forward on my hands and knees. A couple steps further, I did it again, half pulling my right foot out of the boot and slightly spraining my big toe. Soon boots were academic as the mud sucked them off my feet. When we finally made the beach, with the boots in hand, I thought we looked like a couple of extras in an old silent movie farce and half expected to see someone hand cranking an ancient movie camera and a director yelling "cut!" It was hard to tell our foul (now in more ways than one) weather pants were yellow through the caked mud. Fortunately, it was almost midnight, and too dark for anyone to memorialize our ungraceful landing on video. Indeed, the kind shore crew took us to a hose to clean up.

But, more than 40 hours into the 2007 running of the Everglades Challenge, a 300-mile adventure race from the mouth of Tampa Bay to Key Largo. we were at Checkpoint 2, more than halfway to the finish. Incredibly to us, Oaracle, a Jim Michalak-designed Frolic2 sailboat, was running fourth.

If the landing was low comedy, we were soon reminded that an Everglades Challenge is serious business. Catching some rest on the beach were XLXS, Carter Johnson, and Manitou Cruiser, Mark Przedwojewski, who were in kayaks and traveling alone. Sleep was imperative as the tough conditions of the first day and a half had worn them down. Noel and I were feeling relatively fresh, so we decided to depart without a nap. We had no illusions about our ability to stay in front of them for the rest of the race, but for a brief shining moment, we could claim to be second overall in the EC.

It was briefer than expected. We drifted, rowed against tide and wind, and sailed to clear the twisty Chokoloskee Pass in the post-midnight dark. Then in the Gulf of Mexico we promptly ran into the strongest winds of the trip. Aside from the whine in the rigging, there was a moan in the wind we hadn't heard before, and a confused pattern of waves tossed Oaracle like a wood chip. We had double-reefed the sail as a precaution before leaving, but Oaracle still felt overpowered. The waves threatened a broach and the rolling threatened a gybe. Ominous sounds came from the boat as it lurched through the slop.

It was the first time in what had been fairly rugged conditions that Oaracle felt in danger of getting out of control. So we dropped the main and used the mizzen to reach back to the protection of the 10,000 islands south of Everglades City. Eventually we anchored behind Crate Key, next to Rabbit Key. Putting our dry bags in the cockpit, we had enough room to sleep head-to-toe in Oaracle's small cabin, waiting for the winds and waves to die.

So it went for WaterTribe's 2007 Everglades Challenge, a competition for kayaks, canoes, and small sailboats. This year, 37 craft left the beach at Ft. DeSoto Park on the northern side of Tampa Bay. The course takes them 67 miles south to Placida, either via the Gulf of Mexico or the more protected Intracoastal Waterway, site of the first required checkpoint. Another 90 odd miles takes you to the mud of Chokoloskee, the second checkpoint. From there, competitors have a choice of going through the Everglades on the Wilderness Waterway or going around the glades on the Gulf to Flamingo, the third checkpoint. It's more than 90 miles via the waterway and significantly less on the outside route. Some compromise by sailing outside to the Shark or Little Shark rivers and then taking those to Whitewater Bay, following a marked route across that to Flamingo. From Flamingo to Key Largo is the shortest leg, only 34 or 35 miles. But it crosses the shoals of Florida Bay, where in many places navigation is restricted to narrow channels, not wide enough to tack a sailboat. Against the current and wind - and the prevailing winds are typically contrary - it can be brutal for paddled craft and impossible for sailing ones.

Integral to the challenge are the "filters" designed by WaterTribe founder Steve Isaac's, whose tribe nickname is Chief (we all have nicknames; I'm Lugnut and Noel is Root). The first is that all boats must be launched by the crew from above the high water mark - and the race always starts at low tide. Anchors, pulleys, come alongs, etc, are perfectly all right to use, but the competitor must carry all such launching gear for the entire challenge. We used a couple of inflatable fenders as rollers and were able to push the boat to the water. The next filter is at CP 1. To get to the checkpoint, it's necessary to get up a tidal creek passing under a fixed bridge with about nine feet of vertical clearance and 10 feet of horizontal clearance. For sailboats, that means the mast(s) must come down and the boat must be sculled or paddled under the bridge, as it's too narrow for oars. If tide and wind are against you, it adds to the excitement. The remaining filters are just the challenge of getting in and out of the checkpoints, and across the shoals and channels of Florida Bay.

Add to that the weather, which can be nasty in the Florida spring. Veterans counted 2007 as one of the rougher challenges, and about a third of the competitors who launched from Ft. DeSoto dropped out before the finish. There are four classes: Class 1 is for kayaks and canoes with downwind sails only, limited in size to 1 square meter per crew member. Class 2 (including XLXS) is for paddled kayaks and canoes without any sails. Class 3 (including Manitou Cruiser) is for kayaks and canoes with full sailing rigs, including leeboards or centerboards and outriggers or amas. Class 4 is for small sailboats and everything else.

This year Noel Davis, of the FurledSails.com sailing podcast, had agreed to crew with me; ironically I never knew that Noel, wife Christie and their children lived in the Tallahassee area like we did until I invited him after he did a podcast on WaterTribe. Small world.

My wife, Helen (Wingnut is her tribe name, but known to the crew of Oaracle as the Admiral) assumed the role of ground contact and chief cheerleader. She also gave us the terse and oft-repeated orders for the EC: We were to sleep in shifts and in good weather keep Oaracle going 24/7. Noel and I were not sure she would accept shipwreck, alligator attack, or broken bones as an excuse for not pressing on.

Our landing and departure from Chokoloskee was a microcosm of our challenge. There were few easy miles, and the further we went, the harder they got.

Launching day had me in my usual nervous state. The winds the previous two days had been from the southwest, frequently as high as 20 to 25 mph. That's bad as the course down the coast is just east of south. A strong southwest wind means high seas on the outside, being close hauled, and perhaps long and short tacks to make progress. The inside route is restricted by narrow channels and shoals for much of its length, with trees and buildings blocking such a wind in many places.

I contemplated not launching and waiting for more favorable winds, but by the start, Saturday March 3, the wind, as forecast, had swung around to the north and northeast. The velocity had dropped slightly, but was still a strong wind. We left with a reef already tied in the main. The launch morning was the normal last minute rush of loading supplies, getting a group picture, and getting the boat ready. Chief issued a prescient warning: While the water appeared calm close to shore, the strong offshore breeze meant it would get rough quickly. Our last decision was to raise the main while ashore so when we hit the water, we could jump in and go. And suddenly it was 7 a.m. The kayaks headed for the water, and soon so were Roo, Graham Brynes, and Tinker, with Roo's custom designed Everglades Challenge 22 - an impressive sight. We followed Roo to the water and by 7:05 a.m. we were launched and underway.

Chief was right. About a half mile offshore, things did get rough. In front of us, a sit-on-top kayaker in the Ultra Marathon portion of the event (which ends at CP 1) had flipped. Every time he got back on the narrow craft, it rolled over. We rounded up as another kayaker pulled alongside to help. Matt Layden (Wizard) pulled in with his new seven-foot pram, in perfect control. And then another kayak overturned, a few yards further out. We went back to the first overturned one. The rescuing kayak asked us to escort the troubled sit-on-top kayak, its owner acknowledging it was the wrong craft for such a rough day, back to shore. Noel and the kayaker kept a firm grip to keep the kayak alongside and aimed as straight as possible, while we slowly headed back to shore, eventually dropping the competitor about a mile up the beach from the start. Then it was back to the race.

The north wind meant the inside ICW route was practical, and maybe even preferable. The northerly wind tends to funnel through the waterway in the narrow areas, and Oaracle's short mast means there are only two swing bridges and one drawbridge on the way to CP 1 that have to open for her. The cool temperatures and strong northerly wind also kept the powerboat traffic at a minimum, at least until mid-afternoon.

The further we got across Tampa Bay toward Sarasota Bay, the rougher the seas. By the time we crossed, we were surfing down the 3-to-4 foot chop and had caught up with the back end of the fleet taking the inside route. The water calmed a bit as we left Tampa Bay and was positively placid behind an island that protected us from the chop and most of the boisterous wind. Our "five-minute vacation," as we dubbed it, was interrupted by a Coast Guard RIB passing close by, dragging a big wake. The wake rolled Oaracle violently; the worst wake of the entire trip.

As we left the calm and entered the more open Sarasota Bay the waves began to churn up. Helen's report for us on the WaterTribe had it right: Tampa Bay was like being tossed in a commercial washing machine, Sarasota Bay was like a home machine.

Many WaterTribe participants have spoken about hallucinations, and I had them in my first contest in 2004. But a mere four hours after the start, as we sailed through Sarasota, I had reason to worry about Noel when he said there was a boat approaching carrying . . . palm trees. In fairness, it should be noted that Noel's eyesight is much better than mine. But palm trees? It turned out he was right. A barge type boat was outfitted to offer tours of the Sarasota waterfront, including palm trees on the upper deck. We shook our heads.

By then we had passed most of the paddlers who had opted for the inside route; most of the Class 4 boats appeared to have chosen the open Gulf or launched behind us. Once through Sarasota Bay, into Little Sarasota Bay, Roberts Bay, and the channels leading to Venice, the wind eased, or maybe it was just blocked more. We unreefed the sail and continued to make good progress, albeit a bit slower. Some of the faster paddlers, led by Manitou Cruiser resolutely padding and sailing, began to catch us. Then team RAF, two trimarans built by engineering students from North Carolina State University who launched after us, slid by effortlessly. Obviously they had very fast boats. Shortly thereafter, a cluster of kayakers caught up, including Sandy Bottom, mother of one of the RAF team.

(Gary and Neil at Venice) At Venice Inlet, the RAF guys chose to go outside, while we and the kayakers opted for the manmade channel that leads to Lemon Bay. Salty Frog (Marty Sullivan, one of the most skilled, experienced and fastest of the WaterTribe paddlers) snapped a picture as he went past. We settled into a group, sort of an ad hoc team (an inside joke for WaterTribers), consisting of us, Savannah Dan and Paddermaker in a double kayak, Sandy Bottom in her Class 3 sailing kayak, KiwiBird in her Class 1 downwind kayak, and a solo pure paddling kayaker whose name I never got.

The next 90 or so minutes were one of the highlights of the trip as we chatted and cruised down the channel. Oaracle is a spartan craft by sailboat standards, but compared to the kayaks, we were a luxury liner - a contrast that drew some comment from our compatriots. Noel and I tried not to be too ostentatious as we stood and stretched, and talked about having hot cocoa.

As the channel emptied into Lemon Bay, the wind became less blocked and we began to pull away from the paddlers. Stump Pass came abeam and the light began to fade, and by the time we were at the narrow channel at the end of Lemon Bay, it was dark. Dodging a ferry on the way, the channel led to the start of Gasparilla Sound. Following the twisting channel the mile or so to the swing bridge isn't easy in the dark. The bridge tender acknowledged our call, but was a bit late opening, we had to gybe around with Noel at the helm alertly avoiding Manitou Cruiser who had appeared at our side. We finally slid past the bridge, and the gap in the railroad bridge a couple hundred yards further on. Then it was to the flashing red channel light that marked the turn into the side channel that would take us to CP 1. The wind was enough northeast that Oaracle could not sail up the side channel, so we lowered sail. We began drifting back toward the flashing marker, but got the mast and sail down and deployed the oardles (Oaracle's oars, made from a cast off aluminum double paddle) in time - our only mild panic party of the day.

As we rowed up the channel, Savannah Dan and Paddlemaker passed us and we had a pleasant, short chat. We rounded a corner, pulled out the oars to use as paddles under the fixed bridge, reshipped the oars, and what seemed like a few strokes later, Noel was easing us to a perfect landing at Grand Tours in Placida, the eagerly sought CP 1. It was 8:58 p.m., just shy of 14 hours after the start.

Decision time. We hadn't made any long-term plans but left the decision on how to proceed until we reached CP 1. We could go back under the fixed bridge and anchor for the night, or we could press on. We both felt in good shape and had made time during the day to take turns lying down either in the cockpit or below. I don't think either of us actually slept, but we felt rested. We decided to take our time at CP 1, eat a hot meal, go over the chart, stretch our legs, and then keep going. We would also double reef the main, since the wind seemed to be picking up. During the easy parts of the upcoming course when we both weren't needed to sail and navigate, we would take turns at the helm, with the off watch resting below. If we got tired, there were plenty of good anchorages past Cayo Costo, on the south side of Charlotte Harbor a few hours ahead. Otherwise, we would continue down Pine Island Sound.

The plan worked. We were each able to get rest below as we headed south. While I don't think either of us slept soundly, we both dozed and we never felt tired. We were also glad for the double reef - our speed stayed around 5 knots despite the reduced sail.

The closer we got to Charlotte Harbor, and the mouth of Boca Grande Inlet, the rougher the water, not surprising since there were miles of fetch for the waves to build up in the north-to-northeast wind. Noel was below and he soon came up to marvel at the motion. We agreed it was our third "washing machine" of the day. The water settled down as we got around Cayo Costo. Since we both had had some rest and still felt fresh, we continued on down Pine Island Sound, taking turns steering and resting. By early morning, we had reached the sound's south end where the ICW jogs east. The winds went light and we had to do some long and short tacking, once scraping the bottom with the leeboard when we got south of the channel. With the weather forecasts calling for strong winds, we decided to leave the double reef in rather than do a lot of sail handling in the dark. About sunrise, we rounded the corner in the channel and bore off for the entrance of San Carlos Bay, with the wind picking back up. By midmorning, we had scooted under the west side of the causeway over the bay, headed ESE to the channel and headed out into the open Gulf. The directions for the next few hours were easy: keep Oaracle a couple miles off the shore and head south. The winds were on the verge of where we could shake out one reef, but we decided for the moment to leave things as they were. Seas were 3 to 4 feet and we were making 4 to 5 knots. We used the time to eat, check charts, and again catch up on rest. Neither of us had yet managed any real sleep, but we weren't feeling tired. Our rest periods and short naps seemed sufficient. Shortly after 2 p.m., with Noel below, the seas had calmed enough to try the tiller locking system Chuck Leinweber had suggested the year before. It held course very well if we didn't move around or the seas weren't too rough. Unfortunately, that the seas were low enough for the tiller lock to work well meant the wind was easing. Although the forecasts still called for strong winds, our speed was down to between 2-3 knots. At that pace, we wouldn't reach Cape Romano in daylight, which I wanted to help us through that area of shoals. With Noel snoozing below, I decided to give the tiller lock an acid test. I set it on course and then went to lower the main and shake out both reefs. Amazingly, the lock kept Oaracle acceptably on course while the sail was eased and lowered, the reef points undone, and then reraised. Noel, who got up as the sail was being hoisted, couldn't believe it. But we did it again the next day when taking out a reef. Adding sail proved to be the right choice, as our speed picked up to between 4 and 5 knots, and sometimes higher. Cape Romano now looked easily doable in daytime.

The winds stayed moderate, but the seas picked up as we passed Marco Island, enough that we started surfing again and I began to think a reef might be necessary. But when we passed Coxambas Inlet, on Marco Island's south side, the seas immediately calmed. Apparently the bottom had shoaled on the north side, even out to the half mile or so where we were offshore at the time. Things stayed favorable - this was to be our longest stretch of moderate winds - as we rounded Cape Romano. We dragged the leeboard tip a time or two and had to take a couple short tacks around a visible shoal, but otherwise it was an easy passage. Noel took the helm and I went below to get some rest, and the sun set behind us. Ahead 10 miles or so was Indian Key Pass and the entrance to CP 2. I came up as Noel brought the flashing green light marking the entrance to the Indian Key Channel in sight. We caught a break entering the channel, which heads about NNE for the first part. The winds had been predominantly northerly or northeasterly, but at the moment they had backed to west of north. We could just lay the course and made the first leg without tacking. The rest was fairly straightforward, until the mangrove islands blocked the wind about halfway in. Out came the oardles and we rowed when the wind died and sailed when it filled in. Towards the end of the channel we were overtaken by a paddler, XLXS. Exhausted by the rough conditions, Carter talked of crossing Charlotte Harbor, probably a few hours ahead of us, with waves coming over the bow of his slender craft and smacking him in the chest. Noel and I shuddered at the thought. As he paddled ahead into the dark, Carter said he needed at least four hours of sleep to recover from his physical depletion. Noel and I looked at each other. We figured if we were in his state, we'd need more like four days. We reminded ourselves that Carter holds the 24-hour world distance record for paddling a kayak.

(Carter Johnson)

(Carter Johnson's XLXS)

Soon the channel brought us to the north end of Chokoloskee Bay, and we turned south for the final run to CP 2, and our date with the mud and then the high winds. We landed at 11:30 p.m. on Sunday.

One of the reasons for the quick departure was the glimmer of hope for an even better finish than we achieved. I calculated if we had a perfect run down the Everglades coast and into CP 3 at Flamingo and had a fast turnaround, we might have enough daylight left to get through the treacherous channels in Florida Bay, if we had a favorable wind. As long as we cleared the channels before dark, we could beat if necessary to the finish at night I had ruled out trying the channels in the dark as the markers are unlit (some have reflective tape, some don't), and the channels are narrow and one is named Twisty Mile for good reason. At best it was a slim chance, but we didn't want to rule it out.

We cleared Chokoloskee Pass between 2:30 and 3 a.m. and after our adventures with the wind, anchored at Crate Key around 5 a.m. We didn't bother with an alarm, because now it would be Tuesday during daylight before we could attempt Florida Bay. We slept until around 10:30, rising stiffly. The order of the day was to take our time getting underway. The wind was still brisk, but it had dropped from the previous velocity. The underlying moan was gone. And after two days of mostly clouds, the sun was finally out. We heated water for breakfast, changed clothes and got ready for another day. While we were eating, Manitou Cruiser passed by a mile away, heading south under sail. We finished our preparations and followed around 12:30 p.m.

It was to be a symmetrical day. We started out double reefed and after a couple hours, the wind eased and we shook out a reef. A couple more hours, it eased a bit more and we took out the last reef. Our speed stayed at 5 to 6 knots for most of the day and we made good progress - it was to be our last bit of easy sailing. The wind began to pick up and one reef went back in by late afternoon. The sun set as we went by Middle Cape at Cape Sable, and the wind blew stronger. A bit later we watched the moon rise over the peninsula. After rounding east cape and heading east and clearing Middle Ground Shoal, where the water was more protected, we put in the second reef. Once past Middle Ground Shoal, we couldn't quite lay course for the channel into Flamingo, and a couple short tacks were required.

We paid close attention to the compass as a course of 70 degrees would be required when we hit the first couple of channels in Florida Bay - and we were just doing that. If the wind were northeast, we wouldn't be able to sail in those long channels, and a long detour around Florida Bay - and probably another day on the water - would be required. We were just making 70 degrees, which took us to the Flamingo channel about one third of the way in from the outer flasher. We struck sail and rowed the mile or so into the harbor, arriving around 2 a.m. It took a couple hours to find the lock box and sign in, find the restrooms, get the boat tied up at the dock for the night, and get something to eat. By 4 a.m., we crawled below to get a couple hours sleep, vowing to be up and moving at first light to take advantage of the wind, if it held.

And it did. We were up at 6:20 and underway an hour later, fortified by a couple cups of hot chocolate Noel bought at the local convenience store. We spotted Manitou Cruiser at the launching ramp, preparing for the day. He had gotten in a couple hours before us, camped nearby, and was now packing and stowing. His sailing rig and outriggers were stored; Mark would paddle into the winds and currents on the last day.

(Mark)

(Mark and Manitou Cruiser)

A little rowing soon had us out of the harbor, into the channel with the sail up. We reached Tin Can Channel a few minutes later . . . finding we could hold course to the ENE for the first critical leg, after which the channel curves to the ESE and then east.

A highlight was encountering an osprey on one of the channel markers, clutching a sizeable fish. Obviously, he thought we wanted his fish and every time we came up to a marker, he took flight for the next one, deaf to our assurances we didn't want sushi for breakfast.

By 9 a.m., we were almost through and I was feeling a bit cocky about our prospects. Florida Bay provided a reminder it is not to be taken lightly. We had just passed Buoy Key when we hit a narrow area of the channel where the water was no more than a foot or so deep. We could keep the sail full, but with the leeboard almost completely up, the leeway set us over to the south bank. From the boat, Noel used an oardle to lever the bow off the bank and we turned downwind into deeper water and gybed around to try again . . . and again . . . and again.

For the better part of an hour we failed to catch a favorable slant or at least find a deeper part of the channel, always ending in the mud. Finally, I remembered that sailboats sometimes used their motors to help reduce leeway. We didn't have an engine, but we did have oars. We fell off the bank again heading downwind, deployed the oars, and gybed around again for another attempt, with me at the oars and Noel at the helm. We slid through on the first attempt. I reflected on my tendency to learn valuable lessons the hard way.

We were ready for Dump Keys and their channel. The wind held and a few strokes of the oars eased us through between the two keys where the wind was mostly blanketed. Although the chart indicates a channel after the Dump Keys, we found it a wide, shallow area, albeit with enough depth to use all or most of the leeboard, with the markers limited to a couple shoal areas shown on the charts. We also noted that the wind had shifted and was heading us. It was now difficult if not impossible to hold a true easterly course, and we had to make a couple short tacks to clear End Key so we could bear off to the southeast and Twisty Mile Channel.

Twisty Mile now worried me. Although it generally trends to the ESE, it's well named with lots of twist and turns in its length. We would be required to head east, and maybe a little north of east for some short distances, courses that now looked iffy. The approach was made at battle stations, with the oars out and ready to go. And we actually did pretty well, making it about halfway through. But a channel turn to the east, the 15-20 knot headwinds, and an adverse current of at least a knot and probably more, did us in. With the main slatting, we couldn't make progress under oars, and so beached on the north bank to consider our options.

First we lowered the main and tried rowing, but still couldn't make progress. Noel got out and tried towing, sinking almost to his knees in the muck. I reluctantly got out to help push, but after only a few yards, it was obvious this was too hard. I had told Noel walking 50 yards in the Florida Bay muck was like running a mile on land; after his first-hand experience he accused me of underestimating the difficulty. We beached the boat again to catch our breath and consider our options.

Manitou Cruiser caught up to us at this point, efficiently moving with his single paddle, he paused for a few minutes to chat. He, too, found the conditions rugged, but he planned to plug on and finish.

I was getting concerned about our prospects. It was now about 2 p.m., and we were still stuck in Twisty Mile. Even assuming we got free soon, we would have to beat to Jimmie Channel against wind and tide, get through that, and then beat to Manatee Pass. With the wind shifted more easterly, we should be able to sail through Manatee, but we needed daylight to do it - and the sun would set around 6 p.m. And with the necessary double reef in the main, Oaracle doesn't point as well as she does with an unreefed or single reefed sail. We really had only two choices: Drop the mast and try rowing again with the reduced wind resistance (the mizzen had to stay up to help keep the bow pointed into the wind), or wait a few hours for the current to change direction - and count on anchoring that night in Florida Bay.

Since we would have to wait anyway, there was nothing to be lost by dropping the mast. We shoved off again, and it was like Chokoloskee Pass again, only slower. We managed headway, but often only inches per stroke. Occasionally, we would catch an eddy or get out of the worst of the current and we might make a couple feet per stroke. Slowly, we inched our way to the end of Twisty Mile, a passage that probably took 30 minutes but seemed a lot longer. (We were passed by a power boat during this part whose skipper actually knew about the Everglades Challenge and what we were doing.) Then it was up mast and up sail and beat to Jimmie Channel. At least we now knew what to do. We actually sailed a couple hundred yards into Jimmie but lost most of it drifting back when we tried to lower the sail, so we sailed in again and anchored while we took the sail and mast down. The GPS recorded 35-40 minutes of rowing time, with speeds varying between 0.0 and 1.2 mph, probably an average of under 1 mph. But progress was steady. Nearly to the end, Noel tossed the anchor over, saying we weren't making any headway and it was time for a break. Later he told me the further we went into the channel, the redder my face was getting as I pulled at the oars. He was afraid I was about to blow a gasket and thought a rest appropriate. It helps to have a considerate crew.

After about 10 minutes, the anchor came up and in a few more minutes we were free of Jimmie Channel. There was no good place to beach the boat, so we reached off to the south under mizzen alone while the mast and sail were hoisted, and then began the beat to Manatee Pass, our last real obstacle.

It was now 5 p.m. and we had maybe 90 minutes of light. We arrived at 5:55 and had our last, but fortunately minor, obstacle. We could indeed sail the course through Manatee, but there was a shoal at the entrance that kicked the leeboard almost completely up. In a replay of Tin Can, the leeway set us on the mud on the west side of the channel. Noel levered us off and we headed back out to try again. This time I was sure we could sail through, and on the third try, we made it. We sped off north in the lee of Manatee Key and discussed our options. It had been a tough day, and we could anchor near Manatee and catch some rest before finishing. On the other hand, the weather forecast didn't indicate the 15-20 mph winds would be diminishing anytime soon, and it looked like a long beat to the finish, whenever we did it. "We'll sleep when we get to Key Largo," Noel said.

The next three hours proved to be rugged sailing, hard on the wind in breezy conditions and double reefed. Oaracle handles rough water well, but any flat bottomed boat will do some pounding and each of the closely spaced waves we hit sent a generous portion of spray over the cabin and into the cockpit.

But we did catch a break when the wind, which had at one point seemed to be almost due east, backed to the northeast. We sailed north of Manatee Key far enough to tack and clear it and Stake Key. Then one more tack to the north, and we were able to lay a straight course to the ICW inside of Key Largo. Our course would have taken us almost directly to last year's finish line (and knocked a couple hours off our finish time), but this year it had to be moved a couple miles to the north, in Buttonwood Sound. So we tacked up between the ICW and shore, losing some wind as we closed the beach, and picking it up again when we neared the waterway. A little rowing was necessary to get through the closely spaced mangrove islands protecting Buttonwood Sound, and then it was picking our way through the moored boats (some unlit) outside the finish line. We beached at 11:41 p.m., tired and exhilarated. We were fourth overall, second is Class 4, and had finished on Tuesday, 3 days, 16 hours, and 41 minutes after the start. Our Admiral's orders had been heeded and we had pressed on whenever possible. We earned our sleep.

SOME TECHNICAL THOUGHTS . . .

...Every race is a combination of the experience of doing it and the technical aspects of getting the job done. Here are some technical thoughts and data from our EC 2007.

According to the GPS, we were underway for not quite 69.5 hours - and that may understate it a bit, since it's possible the GPS didn't register some of our slow crawls through the channels and passes in Florida Bay and when leaving Chokoloskee. The moving average was 3.8 knots. Subtracting the times under oars, mostly fighting wind and current, and when we were creeping in and out of checkpoints, it would be a bit over 4 knots - a very good speed for a lightweight, 20-foot boat with about a 16 foot waterline. It's an indication strong winds were about. Chuck Leinweber and I in 2006 estimated that the sails were reefed about half the time we were under sail. In 2007, most of the veteran ECers accounted it as one of the rougher years. Totaling it up, Noel and I spent less than 20 hours with an unreefed sail. Subtracting the hours under oars, we spent well over 40 hours with reefed sails and the majority of that with the main double reefed. The National Weather Service had small craft advisories for most of the time we were out. We hit our peak speed for the trip the first day, crossing Tampa Bay, at 9.7 knots. (Oaracle's all time record is 10.8 knots from the 2006 EC). The second day we had a burst to 9.4 knots and we had spurts to 8.5 and 8.8 knots the third day, running down the Everglades coast. For all that, we only felt overpowered once, on Monday morning coming out of Chokoloskee.

Oaracle proved itself well up to the task. Jim Michalak designed it for rough water and it certainly proved it can handle that. There were only two minor items of damage. One is in the lightweight foam and fiberglass hatch I designed to cover the cabin slot top, which I cracked when I leaned heavily against it once. The other is a small crack in a 1/4 inch ply cockpit seat, which occurred when Noel lost his balance and stepped heavily on it.

Possible changes include adding a small storm trysail for when the winds are too strong for a double reefed main. Under the mizzen alone, we couldn't sail higher than a beam reach and a trysail might improve that. I might also experiment with a Chinese lug, if one can be made inexpensively from a polytarp kit. I don't think it would be as aerodynamically efficient as Oracle's balanced lug, but the enhanced ease in reefing and unreefing might make it a worthwhile tradeoff.

A big improvement this year was having a color mapping GPS, a West Marine Garmin 76 CS Plus, to be exact. Paper charts are still better for a quick overall view, but the GPS proved invaluable. It made it possible for one person to steer and navigate at night - at least in the less complicated parts of the ICW - rather than having one steer and the other watch the chart and pick out the upcoming marks. At night, it was easier on the night vision to check the GPS (the GPS light is adjustable in intensity) rather than turn a flashlight on a paper chart. There were only a couple minor drawbacks. There was a gap in the Blue Chart coverage of Florida Bay, which included most of Twisty Mile and all of Jimmie Channel and Manatee Pass. As on the paper charts, the Florida Bay channels are not completely accurately charted; I wouldn't use a GPS to run them at night unless I had a track and waypoints from a successful daytime run. And a couple times we found spots where there were side-by-side red and green ICW channel markers where the number of the green marker was written on top of the red (flashing in both cases) marker. That made it difficult to see on the screen. A minor annoyance and a reminder to be careful with technological gizmos. But overall it worked so well that Noel took to calling it the "magic box."

Perhaps the biggest surprise for me this year was the terrible conditions in which Oaracle would continue to make progress under oars. If someone had told me before the race it was possible to buck a 1 to 2 knot current and 15-20 knot headwinds under oars, I would have said they were nuts. But we did - albeit at a speed of less than 1 knot. A key is the small mizzen, as Oaracle's bow tends to blow off when rowing in winds of 10 mph or more, and a sheeted in mizzen counteracts that. I am not an expert rower and while in good physical shape for the race, I wasn't in superlative condition. That I could keep Oaracle going in such conditions speaks volumes about the design. As always in such an event, I learned more about handling Oaracle, this time in particular about sailing and rowing at the same time.

(Winner, Graham Byrne)

There's always a debate about the best boat for an EC, and I think this year 's event showed there are a multitude of answers. Look at the finishers in Class 4. Graham Brynes of B and B Yacht Designs designed and a built a special boat for this year's EC. Sailing it superbly, he smashed his EC record of last year by 9 hours. If you take into account a couple of bad breaks that cost him time, Graham has shown that a 48-50 hour EC is possible.

(Byrne's winning Southern Skimmer and Mark Kruger's Manitou Cruiser at the finish.)

We were second in a stock design for home builders and which is intended for ease of construction, low cost, and good all around performance. Next was Team RAF, in their two home built trimarans. They had fast boats and had they not been plagued by some problems (including a broken leeboard) and newcomers' unfamiliarity with the course, they might well have been ahead of us. And there was the always incredible Matt Layden, who finished less than half a day behind us in a eight-foot pram, and with considerably less apparent effort than we expended.

All of the remaining Class 4 boats also were single-handers, and included an inflatable beach catamaran, two Hobie Island Adventurers and a pair of Sea Pearls. (Both double-handed Sea Pearl entrees ran into problems and had to drop out.) In that group, there's plenty of room there for anyone to find a boat they like for an EC.

Finally, it must be pointed out that sailors have a different race than the paddlers. This year was probably the most physically challenging, protracted event I've ever done, yet the energy I expended was likely only a small fraction that any one paddler used in completing the course. One thought I had during the EC is that while we are divided into four classes, each boat and each crew forms a unique combination of traits and abilities, and that every vessel is really in a class of one. The competition is to deal with the water and weather, and complete a safe and efficient voyage. Everyone who does that is a winner."

CHUCK LEINWEBER OF WWW.DUCKWORKSMAGAZINE.COM ADDS...

Jim:

I assume you are going to post Gary?s Everglades Challenge story and I wanted to make a point that he may have not have stressed: these guys were the first amateurs across the finish line. Not to take anything away from the first three finishers as they did amazing jobs, but they were all professionals with professional agendas. The winner is an accomplished boat designer and long time racer who has won this before and designed and built a boat just for this race. He sells these designs and it behooves him to show that they are fast. Second was an Olympic athlete in a kayak so narrow and fast that if you stop paddling, it falls over. Last year he set the world record for distance covered in a paddle boat in 24 hours. Third place, and he bet our guys by only 2 hours and one minute, went to a fellow who builds and sells high dollar Kevlar expedition canoes and who no doubt has a reputation to uphold. These are all exemplary efforts but if you examine them, you see just how remarkable Gary and Noel?s effort was.

Chuck

FINAL COMMENTS FROM ME...

The more I read this story the more I am convinced that Gary's success was not dumb luck. He made all the right decisions that were suitable for his boat and his boat was suitable for the trip. This was Gary's third try, I think, each year more successful. Being even more successful will be quite difficult because it appears to me that the folks that finished up with him are even more experienced!

I say this because a lot of folks don't realise the degree of experience needed in long and open water cruises. Even with experience you can get in a lot of trouble. You might say, "I just get a more capable boat." but the trouble with that idea is that you will eventually still get in trouble only in even worse conditions.

Gary's Frolic2 appears to be to be totally stock except for the little mizzen he added. (My feeling about mizzens is that if you cruise you should have one, if you daysail you shouldn't. Most boats can have one added straight away without changing the main, as Gary added one to Frolic2).

Finally, WHAT STORY! "SO GIVE THREE CHEERS AND ONE CHEER MORE FOR THE MIGHTY CAPTAIN OF THE...."

NEXT TIME...

...we take another look at rowing geometry.

FROLIC2

FROLIC2, CUDDY MULTI SKIFF, 20' X 5', 400 POUNDS EMPTY

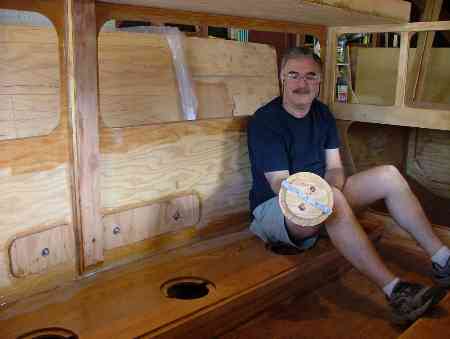

The photos show the prototype Frolic2 built by Larry Martin of Coos Bay, Oregon. Larry built the boat quite quickly this past winter including sewing the sail to the instructions given in the plans. He reported sailing it for the first time on a ripping day with an occasional 2' wave. I always advise testing a new boat in mild weather, especially a new design, but Larry got away with it. Looking at his photos, the neat work, and simple efficient rigging suggests to me that Larry has been sailing small boats a long time.

Frolic2 has a small cabin, probably only for one to sleep in because the multichines that make the boat good in rough water also rob you of floor space. To say it another way, the nice big floor space of a flat bottomed sharpie is what pounds in rough water and makes you uncomfortable. But Frolic2 has a 6' long cockpit so someone could sleep there too. There is bench seating. The cabin top has a slot top down the center and you can stroll right through the cabin standing upright in good weather and out the front bulkhead to the beach. The mast is offset to one side so you will need not have to step around it. Phil Bolger showed us how to do this about 15 years ago and it works. But Larry went conventional with his boat, mounting the mast on centerline and decking in the front of the cabin. On a slot top cabin you use a simple snap on tarp to cover the slot in rain or cold or bugs.

Frolic2 was designed for rough water, long and lean, especially in the bow, and with multiple chines. She's really a takeoff of my Toto canoe in shape. Larry omitted the motor well you see in the lines, and the oarlocks too (The wind must blow just right all the time in Oregon?) but I intended this to be a multi skiff sort of boat with rowing and motoring abilities. You can't row a boat of this size in any wind or waves but in a calm you can travel far if you have patience. I didn't fool around with a gadget motor mount - I put the motor well right in the middle and offset the rudder instead of the other way around. This worked out very well on the high powered Petesboat. We'll see how it goes on a narrow boat because the second prototype is getting the blueprint well as you see in the photo below of the Colorado Frolic2 still being built. You need little power on a boat like this, 2 or 3 hp is more than enough.

The lug rig is for quick easy stowing, rowing, and towing. (The blueprint sail is actually the same size and shape as that of a Bolger Windsprint, a boat which weighs maybe a third as much as Frolic2 and is much narrower. But I think the Windsprint might be over sparred for its size and weight.) Larry reports the rig is about right for the boat, sailing fine with a reef in and three adults on a windy day. The lug sail can be closer winded reefed than when full, perhaps because the sail is then shorter and the yard better controlled (less sail twist). For that matter a sharpie sprit sail the same size as the lug might be smarter in rough water conditions if you can live with the long mast. Switching rigs won't be hard. The mast can be relocated almost anywhere in the slot top without altering the hull to any degree. You just need extra partner and step fittings.

Update, 2006. Jeff Blunk's Colorado Frolic2 eventually found its way to Illinois and then to our Rend Lake Messabout in the hands of Richard Harris. We had a chance to try it out and I was quite pleased. It was fast and powerful. At one point with three men on board, with Max at the tiller, I went forward to tweak the sail which took a couple of minutes with me staring up at the sail. That done I looked back and saw that we were really rolling along.

And Gary Blankenship's Frolic2 completed the Everglades 300 mile challange with him reporting sailing for hours at 7 knots or more. Here is Gary's Frolic2:

Construction is with taped seams from eleven sheets of 1/4" plywood and two sheets of 1/2" plywood.

Plans for Frolic2 are $35.

Prototype News

Some of you may know that in addition to the one buck catalog which now contains 20 "done" boats, I offer another catalog of 20 unbuilt prototypes. The buck catalog has on its last page a list and brief description of the boats currently in the Catalog of Prototypes. That catalog also contains some articles that I wrote for Messing About In Boats and Boatbuilder magazines. The Catalog of Prototypes costs $3. The both together amount to 50 pages for $4, an offer you may have seen in Woodenboat ads. Payment must be in US funds. The banks here won't accept anything else. (I've got a little stash of foreign currency that I can admire but not spend.) I'm way too small for credit cards.

I think David Hahn's Out West Picara is the winner of the Picara race. Shown here on its first sail except there was no wind. Hopefully more later. (Not sure if a polytarp sail is suitable for a boat this heavy.

Here is a Musicbox2 I heard about through the grapevine.

We have a Philsboat going together in California. You can see the interior room in this 15' boat:

And here is another Philsboat in northern Illinois:

HOLY COW! A Jukebox2 takes shape in Minnesota. Unheated shop means no work during the winter. Check out that building rig!

And the Vole in New York. Going very quickly but most likely there will be little more done during the cold winter.

AN INDEX OF PAST ISSUES

Hullforms Download (archived copy)

Plyboats Demo Download (archived copy)

Brokeboats (archived copy)

Brian builds Roar2 (archived copy)

Herb builds AF3 (archived copy)

Herb builds RB42 (archived copy)