We're not in Kansas anymore! Bob Enninberg sailed his new Scram Pram out in British Columbia last summer.

Contents:

Contact info:

Jim Michalak

118 E Randall,

Lebanon, IL 62254Send $1 for info on 20 boats.

Jim Michalak's Boat Designs

118 E Randall, Lebanon, IL 62254

A page of boat designs and essays.

(1April2011)This issue review methods of calculating displacement. The 15 April issue will review rigging a sharpie sprit sail.

THE BOOK IS OUT!

BOATBUILDING FOR BEGINNERS (AND BEYOND)

is out now, written by me and edited by Garth Battista of Breakaway Books. You might find it at your bookstore. If not check it out at the....ON LINE CATALOG OF MY PLANS...

...which can now be found at Duckworks Magazine. You order with a shopping cart set up and pay with credit cards or by Paypal. Then Duckworks sends me an email about the order and then I send the plans right from me to you.

Figuring Displacement

THE VERY BASICS...

One of the real basic errors in boat design is to not match the capacity of the hull to the weight it needs to carry. It's actually pretty easily done. Let's take an example: a fellow wants a 12' skiff to handle two adults. He figures the empty boat will weigh 120 pounds and the adults together at 350 pounds. So he has to float a total weight of 470 pounds.

One thing is for sure: no matter what the shape of the hull, it will sink into the water until it pushes aside, or displaces, 470 pounds of water. (The way I heard it was that ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes figured out the basics while sitting in the bath tub.) Fresh water weighs about 62 pounds per cubic foot and salt water usually about 65 pounds per cubic foot. So the volume of fresh water displaced by the 470 pound boat is 470/62 = 7.6 cubic feet. That was easy!

Next the problem becomes one of shaping the underwater part of the hull such that it displaces 7.6 cubic feet with good flow lines.

METHOD 1: THE PRISMATIC COEFFICIENT...

We talked about the prismatic coefficent a long time ago and you should be able to look it up in the way back issues index. Basically we construct a prism with the same length as the waterline length and the same cross section as that of the boat's maximum beam. The hull will fit neatly into the prism. Divide the volume of the underwater hull by the volume of that prism and you have the prismatic coefficient.

What is interesting to me is that the prismatic coefficient doesn't vary much from one displacement hull to another, as far as normal small boats are concerned. Jewelbox, with a flat bottom and squared off ends, has a prismatic coefficient of about .60

And Toto, with very pointy ends and multichine cross section, has a prismatic coefficient of about .50

So I figure if you were to assume a halfway normal displacement hull has a prismatic coefficient of .55 then you would always be within 10% which is actually pretty good.

So without drawing a line I might say that the 470 pound weight will need a "prism" with a volume of 7.6/.55 = 13.8 cubic feet. The prism could have any combination of cross section and length that will have that 13.8 cubic feet total volume.

Remember that the prism has the same length as the hull's waterline length and underwater cross section as the boat's maximum cross section. Remember we want a 12' boat, but the waterline will be shorter if we want some rake to the ends (for looks) and maybe enough rocker to make sure the stem and stern don't drag the water (for low drag). We might guess that the waterline length will really be about 10'. Then the maximum cross section would have to have 13.8/10 = 1.38 square feet of area below the waterline. If we wanted a flat bottom 3' wide (wide enough to have sailing stability and narrow enough for reasonable rowing) we would have a draft of approximately 1.38/3 = .46' or 5.5".

If we wanted a different cross section than the simple box shape I'm assuming here, we would have to tinker a bit. Draw up a cross section with the 1.38 square foot cross section and see if we like it. Actually in this case I'm going to flare the sides out to 4' at the top of the wale at the cross section. But that won't affect the area under the waterline much. We might sketch out something like this:

METHOD 2: THE CURVE OF AREAS... This method of the "curve of areas" is an accurate and flexible way of determining the volume of almost any oddly shaped thing. It's actually pretty easy to do but first you need a drawing of the proposed boat (unlike the prismatic coefficient which just needs a general idea of the boat).

Let's take our proposed boat and draw a line on it that represents 5.5" draft, our guess at what is needed to float 470 pounds. Every now and then along the length of the hull we take cross sectional cuts of the hull and measure the area at each cut below the 5.5" waterline. The cuts can be taken anywhere but there must be enough to get a good definition fo the hull. Actually for a normal boat about five cuts will do. The more you take the more accurate your work but five will get you really close. Our example boat might be like this:

The dimensions of the underwater sections are measured right off the paper drawings and the area of each is calculated like this:

Next we graph those underwater areas spacing them the same distance apart as they are on the real hull to get the "curve of areas" like this:

The area enclosed under the curve of areas is a volume and is indeed the volume of the underwater hull - it's what we are looking for. In the old days you would measure the areas with a planimeter, a clever and expensive gadget. But you can do well by just breaking down the curve into triangles and trapezoids, figuring the area in each trapezoid, and adding them all up. In the example, second trapezoid from the left is figured by 1/2(175+209)X12 = 2304. Adding the sections together gives us a total of 12500 cubic inches at 5.5" draft. That equates to 7.2 cubic feet of displaced water which is 450 pounds of fresh water. So the first guess was off by 20 pounds or about 4%. By the way, the drawing showed a waterline length of 9'5" instead of the first guess 10'.

As mentioned before this method can be used to figure the volume of almost anything. Let's say we wanted to find the weight of a mast. Say the mast is 24' long, 3.5" in diameter at the base and 1.5" in diameter at the top, with a curved taper between. The figuring of the volume might look like this:

1920 cubic inches equals 1.1 cubic feet. Wood usually weighs 25 to 35 pounds per cubic foot. At 30 pounds per cubic foot the mast would weigh 33 pounds.

You can also use the area of curves to find the CG of the object, too. For real simplicity I've seen designers in the aircraft industry draw the curve on cardboard, cut it out and balance the thing on a knife edge. The item's CG will lie on that balance line.

THE COMPUTER METHOD...

Finally you can use your computer to figure it all out. I'm sure all of you know that getting the computer to spit out the right answer might take a lot longer than doing it by hand. The program I used to get the drawings above was Hullform6s which can be downloaded from the links shown at the end of this page. What were the answers that Hullform6s predicts for the 12' skiff with 470 pounds displacement? 5.5 " draft, waterline length of 9'4", and prismatic coefficient of .55! So the first guesses were quite good. But the area of curves method was also excellent, within 4%. It showed the same waterline as Hullforms. Perhaps with more data points to flesh out the curve the hand method would get the same answer as hullforms but I wouldn't bother. You will never guess the weight of the finished boat within 4%.

Marksbark

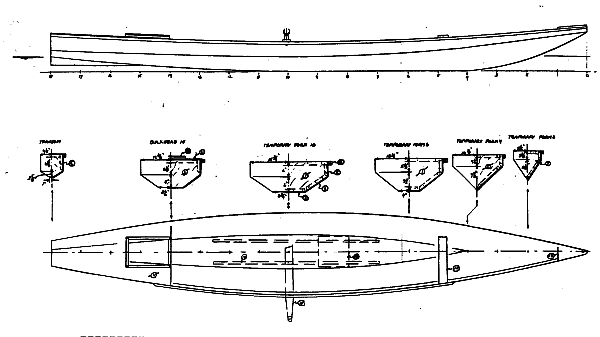

Marksbark, Fast Rowboat, 18' X 3', 90 POUNDS EMPTY

This long narrow boat was designed a long time ago for Mark Bustemonte who thought it might be possible to have a boat for fast sliding seat rowing, for slower fixed seat rowing with a passenger, and maybe for use as a canoe by kids.

I agreed with the idea. I had already once rigged Toto with outriggers and oars. Toto is too short to take a sliding seat. She was a bit faster under oars than with paddle - you can get lots more muscle behind oars and I think the oars are less tiring. But the low slung oars were a problem in rough water and I suspect that is a problem with all low sided rowboats. Also I didn't think the extra speed made up for the extra gear involved and having to watch my own wake instead of seeing what's up ahead. For sneaking up on wildlife and such, the double paddle or kayak has it all over any type except for maybe an electric. Anyway, with the extra length of Marksbark, I think she'll hit 6 mph in good conditions and cruise forever at 4 mph.

It will be interesting to see if Marksbark is stable enough for normal kid rough housing used as a canoe. She's already wide for a sliding seat boat.

Marksbark was drawn well before I put a simple straight plug in the middle of Toto to get a Larsboat. Today I would suggest simply putting a 5' straight plug in the middle of Toto to get the length of Marksbark, long enough for a sliding seat. Instead back then I stretched out the Toto which will probably look more elegant but the prototype builder will have to keep a close eye out to see if the pieces all fit since all this was done before I figured out how to use a PC to give the shapes of the expanded panels. He ought to do what I did with the original Toto - stick it all together except for the bilge panels and then trace the shape of the bilge panel hole onto cardboard and transfer to plywood. The Marksbark plans do give the shape of the bilge panel but as with all multichine shapes it pays to cut that bilge panel well oversized and trial fit to see if the lines are correct. The thing is the last piece of the puzzle catches all the previous mistakes of the builder (and designer!) and a trial fit before cutting to the line is always a good idea.

Marksbark plans are $20 until a prototype is built and tested. Needs four sheets of 1/4" plywood with taped seam construction. No jigs or lofting required.

Prototype News

Some of you may know that in addition to the one buck catalog which now contains 20 "done" boats, I offer another catalog of 20 unbuilt prototypes. The buck catalog has on its last page a list and brief description of the boats currently in the Catalog of Prototypes. That catalog also contains some articles that I wrote for Messing About In Boats and Boatbuilder magazines. The Catalog of Prototypes costs $3. The both together amount to 50 pages for $4, an offer you may have seen in Woodenboat ads. Payment must be in US funds. The banks here won't accept anything else. (I've got a little stash of foreign currency that I can admire but not spend.) I'm way too small for credit cards.

I think David Hahn's Out West Picara is the winner of the Picara race. Shown here on its first sail except there was no wind. Hopefully more later. (Not sure if a polytarp sail is suitable for a boat this heavy.

Here is a Musicbox2 out West.

This is Ted Arkey's Jukebox2 down in Sydney. Shown with the "ketchooner" rig, featuring his own polytarp sails, that is shown on the plans. Should have a sailing report soon.

And the Vole in New York is Garth Battista's of www.breakawaybooks.com, printer of my book and Max's old outboard book and many other fine sports books. Beautiful job! Garth is using a small lug rig for sail, not the sharpie sprit sail shown on the plans, so I will continue to carry the design as a prototype boat. But he has used it extensively on his Bahamas trip towed behind his Cormorant. Sort of like having a compact car towed behind an RV.

And a Deansbox seen in Texas:

The prototype Twister gets a test sail with three grown men, a big dog and and big motor with its lower unit down. Hmmmmm.....

Jackie and Mike Monies of Sail Oklahoma have two Catboxes underway....

Tom Wolf has completed the first Toon2 that I know of and was waiting for some good testing weather...

AN INDEX OF PAST ISSUES

Hullforms Download (archived copy)

Plyboats Demo Download (archived copy)

Brokeboats (archived copy)

Brian builds Roar2 (archived copy)

Herb builds AF3 (archived copy)

Herb builds RB42 (archived copy)