BACKGROUND...

Almost any boat you build from plywood will require panels longer

than the 8' lengths you will find at the lumberyard. For an "instant

boat" the usual manner of joining the panels together to get one long

panel is with a butt strap or butt plate. I've tried lots of

different ways to make the joint in the 15 or so boats I've built

over the years. All the methods worked. I have a feeling that the

butt joints on the usual instant boat hull are not highly loaded and

not too critical to overall boat strength. Since I've tried several

ways and they all worked I've gotten to be pretty nebulous about the

subject on my drawings. Lately I've been specifiying a butt plate as

something like "Butt plate from 3/4" x 3-1/2" lumber, or equal" which

doesn't tell you much. Most builders get by pretty well with just

that but recently one builder asked what in the world I meant, and

rightly so. So let's start the discussion with one joint I've never

tried in plywood.

TRADITIONAL PLYWOOD SCARF

JOINT...

Figure 1 shows the traditional plywood scarf joint. I''ve never done

this in plywood although I've made a lot of scarf joints in plain

lumber. The two overlapping faces are tapered and glued together such

that both joined faces remain smooth. If you are building a

traditional lapstrake boat from plywood you have to make the joints

this way.

What's good about it? The faces are smooth both sides. Essentially

you have a single piece of wood to work with after making the joint.

It's quite strong, as strong as the base wood provided the taper is

long enough. I've seen the taper range from 6:1 to 12:1. The shorter

tapers are easier to make and probably just as good given modern

glues.

What's bad about it? The tapers can be hard to make properly although

thickened epoxy has made experts of most of us. Some experts have

special saw rigs to cut the taper. Most use power hand planes or belt

sanders, I think. When gluing the joint you must press it up against

a firm surface while the glue cures, making sure nothing glues to

that surface, and making sure the two pieces are secured lengthwise

so the tapers don't push them apart as you apply clamping pressure.

There is one more warning for instant boat builders. Almost all

instant boat designs have panels layouts which assume you will not be

using a scarf joint. If you join two 8' panels with a scarf joint you

will NOT end up with a 16' panel. It will be shorter by the overlap

amount. That might be just enought to negate the ply panel layout.

THE PAYSON TEAL BUTT STRAP...

I think this type of joint was described in Payson's great book

INSTANT BOATS. I used it on my Teal which was my first homemade boat.

The side panels were 1/4" thick on my boat, the bottom 3/8". The butt

straps were 3/8" plywood, 6" wide. So the effect of the joint was

similar to a 12;1 scarf on the 1/4" ply sides and about 8:1 scarf on

the bottom. The nails were supposed to be copper, but I think Harold

might have also suggested copper rivets or short bolts for fasteners.

What's good about it? It's pretty simple to visualize and make. If

the fastening is good you can make the joint and go right on building

without waiting for the glue to set. You might do that with the

sides, for example. Another neat thing about this plain butt strap

joint is that, with a typical flat iron skiff type of assembly, the

bottom panels need not be joined before assembly onto the hull. In

that case you will have the hull inverted on sawhorses ready for the

bottom. Then you put the first bottom piece on attaching it to the

sides. Then you install the first butt strap at the end of that

piece. Then you install the next bottom panel to that butt strap and

the sides. And so forth until the entire bottom is planked, like

laying bricks.

I might mention now that I think butt straps and plates should be

well rounded at the ends to avoid trapping dirt and moisture. In

boats that have taped seams I advise stopping the butt strap short of

the edge of the panel so you will have room to run the tapes

undisturbed. This is especially true of butt straps on the bottom.

You must have a clear limber channel around the perimenter of the

bottom. In that case I stop the strap about 1/2" short of the side,

fill the little gap with epoxy to keep the water out, and tape over

the bottom of the joint with glass tape and epoxy. Usually I don't

put glass tape over the outside of the side panel joints. But butt

joints in any deck should be well sealed with glass and epoxy. Here

is an end view of the treatment:

What's bad about the plywood strap? I think in Maine you aren't a man

until you've made a boat with clenched copper nails or rivets. Not so

where I live, can't buy them any place I know of. I got by with

bronze boat nails but they really aren't flexible enough for the job.

They didn't look too cool. And the edges of the plywood butt straps

don't look too cool either, wanting to have gaps and splinters

showing. It takes a while to finish them. And, of course, you have a

lump at each joint and folks will ask, "What's that?"

By the way, when I built my Toto I used the simple plywood strap

method with no fasteners. Just carefully lay the ply panels over the

straps which were well buttered with glue, weighed it all down with

concrete blocks to provide pressure, and stayed away for a few days

until I was sure the glue was totally set.

THE BIRDWATCHER BUTT STRAP...

When I built my Birdwatcer in 1988 I think I piled on more layers of

plywood straps such that I wouldn't have to bend over the nails. And

by that time I was more expert at finishing the edges of plywood. It

worked but it was very obvious that I could have done the same thing

with regular lumber and saved a bit of work.

THE LUMBER BUTT PLATE...

This is what I like to advise now. Not much to it. Very quick and

easy to make. Some say it looks too clunky for their tastes.

If there has been any structural problem with the above butt plate it

is at the ends of a plate that joins bottom panels, ending short of

the sides to allow a limber path. If the ends of the plate are not

solidly glued and fastened to the bottom panels the butt plate will

eventually loosen at the ends. I think that is due to the rapid

change in flexibility in the system where the plate suddenly ends. A

better solution might be to taper the end of the bottom butt plates

starting maybe 3" in from the end of the plate and tapering down to

maybe 3/8" thick at the ends. That will allow a gradual change in the

flexibility and prevent a stress riser at the end of the butt plate.

By the way, for any bulky butt joint care must be taken in design to

see that the joints don't fail in places where the butt plate will be

in the way.

LIGHT FIBERGLASS BUTT

JOINTS..

Both Harold Payson and Dave Carnell presented this one to U.S.

readers in the '80's but I'll bet the English inventors of taped seam

boats did it earlier. Simple as can be in theory. Just a layer of

fiberglass on each side of the plywood.

Dave Carnell presents

lots of details at his web site. He has done scientific load tests of

these joints and says the joint will be as strong as the base wood if

you use one layer of fiberglass cloth in epoxy on each side of 1/4"

plywood, two layers on 3/8" plywood, three layers on 1/2" plywood,

and four layers on 3/4" plywood.

I used the glass butt joint on my Roar rowboat but went back to

wooden butt joints later. At first it would appear that the joint is

easily made by laying the ply pieces on the floor, taping one side

with fiberglass, waiting to cure, flipping the panel and repeating on

the other side. But I found that plywood on its own often does not

want to lay flat enough to get a smooth fit, so I had to place the

joint over a board and screw the pieces down flat. Next the idea of

flipping the panel with only one side taped doesn't work well because

that one layer of glass has little strength by itself. But it can be

done carefully. Better yet is what both Payson and Carnell advise:

glass both sides at once. Lay the first side of fiberglass layers wet

with epoxy on a protected flat surface, lay the plywood to be joined

upon it, lay the second side of fiberglass over the top of the joint,

cover with plastic sheet and weigh down with concrete blocks. The

plastic sheeting not only protects everything from gooey epoxy, but

it should provide a smooth final finish and if you are lucky no

filling or sanding required afterward.

THE PAYSON HEAVY GLASS JOINT...

Harold Payson did a little more work on the glass butt joint. I'm

doing this from memory and hope I'm getting it right. To hide the

build up of glass on a thicker sheet of plywood he recessed the

surfaces roughly with a sanding disk in a drill. Then he added a

layer of light fiberglass matt to the wood before pasting in the

glass. Fiberglass matt is generally thought to provide better

adhesion to wood than glass cloth although by itself it has little

strength. Harold is big on using polyester resin on his boats instead

of epoxy so perhaps the matt is more important for the polyester

users. But you can see the advantage of the system: the final joint

can be more or less invisible as the multiple layers of glass are

recessed.

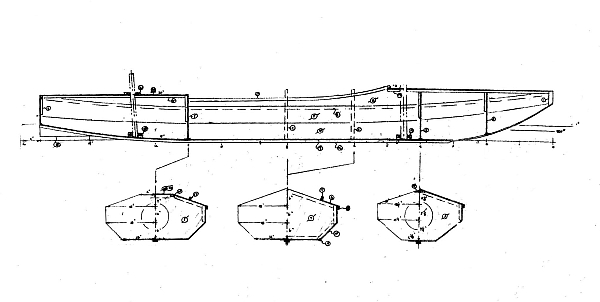

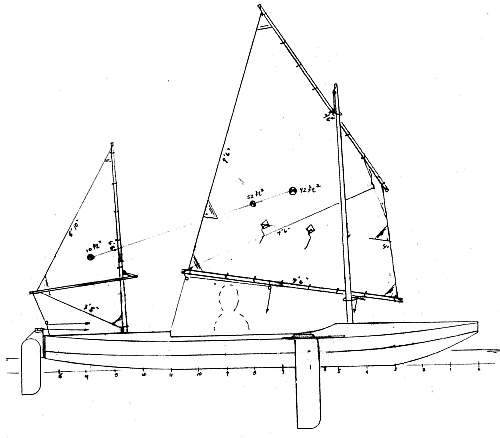

Paulsboat

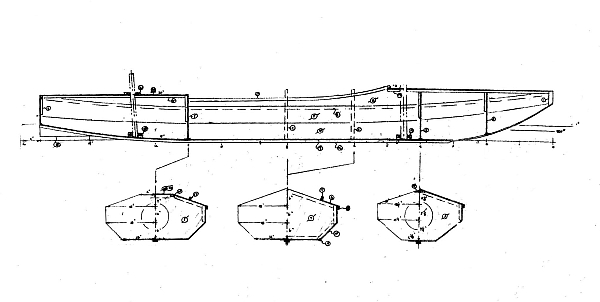

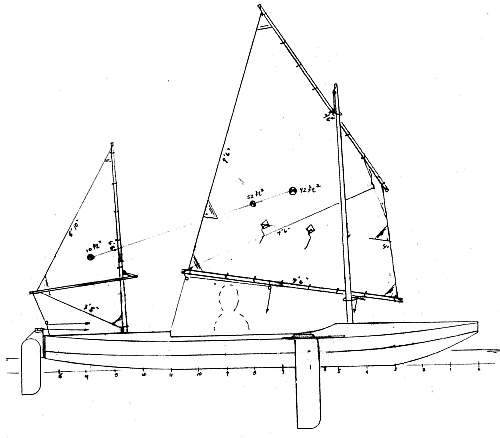

PAULSBOAT, SAILING CANOE, 15' X 3', 120 POUNDS EMPTY

I had a request from Paul Moffitt, of the famous sailing

Moffitts, for a sailing canoe. Now, a "sailing canoe" can mean a

lot of different things. But to me the sailing canoes that you

read about from the late 1800's were what we both had in mind. I

had always put off designing one because I had the idea the usual

sailing canoe design is too wide to be good with a paddle, and

too narrow to be good with a sail. Many of the old classic

sailing canoe designs were actually small decked over rowing

boats that were wide enough to sail with some stability. I guess

there were still called canoes because of their double ended

shape and perhaps because they had recently evolved from true

canoes which were rigged with small sails.

Anyway, it was going to be a compromise. Paul also wanted some

capacity to carry some camping gear. So I drew Paulsboat. It was

really based on my Larsboat which in turn was based on my Toto

which in turn was based on the Bolger/Payson multichine canoe,

etc. To get more sailing stability and more capacity Larsboat was

widened from 30" to 36" and the bottom plank also widened 6". I

gave the cockpit a 7' long open space with the idea that the

skipper could camp inside the boat, which by my experience is

quite superior to sleeping outside. For one thing setting up a

shore tent will usually quickly bring down the law almost

anywhere and sleeping inside discretely will not. I slept in the

smaller Toto many times. Anyway, the cockpit is large enough to

float two adults and is between buoyancy/storage chamber fore and

aft. Access to these chambers might be difficult. I've shown them

with large deck plates in the bulkheads but you likely won't be

able to reach way down in them. I've noticed many folks put

several smaller deck plates in the decks, as Paul did, to allow

access. The deck plates also allow for airing of the chambers and

if you ever build in a closed box and don't allow for airing you

can expect rot very quickly.

The sail rig was pretty well copied from the old sailing canoes

which often used something similar. I stuck with my usual

leeboard for lateral area and placed it such that the boat should

handle well under main sail alone. The rudder was something to

think over. Many of the traditional canoes had a tiller with

complications used to get the tiller to clear the mizzen mast. I

wanted to avoid all that since it usually means some metal

forming and welding and that will turn off many builders quickly.

What Paul wanted was to be able to steer with pedals and had

aquired from Duckworks some plastic kayak pedals where the pedal

did not pivot but could slide in a groove a total of 14". Well,

let me back up a bit. The rudder drawn simply has a tiller horn

on each side, each 12" long. That might sound long but in reality

it would be like steering with a 12" long tiller and then it

seems way short. The idea was to tie a line to the horns that

looped around the cockpit through pulleys forward such that you

could steer with your hands by pulling on the line. Not an

uncommon idea. The downside I thought would be that at times you

would hardly have enough hands to steer and work the sails. So

Paul got those pedals and installed them connected to that

steering loop. He says it all works fine and he was able to

reduce the length of the rudder steering horns. But don't give up

on the idea of the continuous loop around the cockpit. With the

loop you could let your passenger steer as you take a nap.

We pondered a bit about what would happen in a capsize. With the

decks and flotation chambers it should float high with little

water inside but getting back in could be a challenge. I am

pretty sure you should prepare, and test, a stabilizing system

which uses a float attached to your paddle which is somehow

secured across the cockpit to steady the boat enough to allow you

to enter over the side. Nothing new about that idea. You probably

need to be somewhat strong and nimble.

Paul has been paddling with a single paddle and reports no

troubles. Having the pedal operated rudder would be a big plus

especially with the single paddle. I have a feeling we did a good

job compromising on the width of the boat.

Construction is the usual taped seam requiring six sheets of 1/4"

plywood. It is going to weigh a bit, no getting around that, but

Paul has been cartopping without trouble.

Plans for Paulsboat are $35 when purchased direct.

Contents

Prototype News

Some of you may know that in addition to the one buck catalog

which now contains 20 "done" boats, I offer another catalog of

20 unbuilt prototypes. The buck catalog has on its last page a

list and brief description of the boats currently in the

Catalog of Prototypes. That catalog also contains some articles

that I wrote for Messing About In Boats and Boatbuilder

magazines. The Catalog of Prototypes costs $3. The both

together amount to 50 pages for $4, an offer you may have seen

in Woodenboat ads. Payment must be in US funds. The banks here

won't accept anything else. (I've got a little stash of foreign

currency that I can admire but not spend.) I'm way too small

for credit cards.

I think David Hahn's Out West Picara is the winner of the

Picara race. Shown here on its first sail except there was no

wind. Hopefully more later. (Not sure if a polytarp sail is

suitable for a boat this heavy.

Here is a Musicbox2 out West.

This is Ted Arkey's Jukebox2 down in Sydney. Shown with the

"ketchooner" rig, featuring his own polytarp sails, that is

shown on the plans. Should have a sailing report soon.

And the Vole in New York is Garth Battista's of

www.breakawaybooks.com, printer of my book and Max's old

outboard book and many other fine sports books. Beautiful job!

Garth is using a small lug rig for sail, not the sharpie sprit

sail shown on the plans, so I will continue to carry the design

as a prototype boat. But he has used it extensively on his

Bahamas trip towed behind his Cormorant. Sort of like having a

compact car towed behind an RV.

And a Deansbox seen in Texas:

Another prototype Twister is well along:

And the first D'arcy Bryn is taped and bottom painted. You can

follow the builder's progress at http://moffitt1.wordpress.com/

....

Contents

AN INDEX OF PAST ISSUES

A NOTE ABOUT THE OLD WAY BACK ISSUES

(BACK TO 1997!). SOMEONE MORE CAREFUL THAN I HAS SAVED

THEM. TRY CLICKING ON...

http://web.archive.org/web/20050308025339/http://marina.fortunecity.com/breakwater/274/michalak/alphabetical.htm

which should give you a saving of the

original Chuck Leinweber archives from 1997 through 2004.

They seem to be about 90 percent complete.

BACK ISSUES

LISTED BY DATE

SOME LINKS

Mother of All Boat

Links

Cheap

Pages

Duckworks

Magazine

The Boatbuilding

Community

Kilburn's Power

Skiff

Bruce Builds

Roar

Dave

Carnell

Rich builds AF2

JB Builds

AF4

JB Builds

Sportdory

Hullforms Download (archived copy)

Puddle Duck Website

Brian builds Roar2 (archived copy)

Herb builds AF3 (archived copy)

Herb builds RB42 (archived copy)

Barry Builds

Toto

Table of

Contents