Jim Michalak's Boat Designs

1024 Merrill St, Lebanon, IL 62254

A page of boat designs and essays.

(15 October 2018) We look at small boat rudders. The 1 November issue will make some sink weights.

THE BOOK IS OUT!

BOATBUILDING FOR BEGINNERS (AND BEYOND)

is out now, written by me and edited by Garth Battista of Breakaway Books. You might find it at your bookstore. If not check it out at the.... ON LINE CATALOG OF MY PLANS......which can now be found at Duckworks Magazine. You order with a shopping cart set up and pay with credit cards or by Paypal. Then Duckworks sends me an email about the order and then I send the plans right from me to you.

| Left:

A new Harmonica started in Texas. |

|

SMALL BOAT RUDDERS

BACKGROUND...

Here is an article I wrote a while back that appeared in the great paper magazine BOATBUILDER. I've included copies of it in my prototypes catalog since then. The article shows how I've made rudders for my own small boats.

Where I sail only a kick-up rudder works well. It's not because once a year you might strike a ledge and break off a fixed rudder. It's because our waters are generally shallow and a fixed rudder would require endless fussing on every trip. With the weighted kick-up rudder shown here you just blast along without giving the kick-up blade a second thought.

I have also tried kick-up rudders that weren't weighted, but were held down by lanyards. Nearing a shore or shallow I had to play the thing like a puppet and quickly ran out of hands because the tiller, sheet, and board all needed handling at the same time. The weighted rudder blade is much better. In this article I'll show you how I build a kick-up rudder from the ground up from plywood. This sort of rudder can be suitable for boats up to about 22 feet length.

RUDDER BLADE...

The best way to make the blade is to laminate it from thinner plywood. I've seen warped blades made from a single piece of 1/2" plywood, but I've never had a problem with a blade built up from two layers of 1/4" plywood.

Cut out the plywood blanks and butter one up with glue. I prefer plastic resin glue. It comes as a dry powder and is mixed with water to the consistency of regular white wood glue. It's best to spread the glue with a notched trowel like you use to paste down floor tiles. Place the glued-up blanks together on a flat surface protected with plastic or paper, and tap a couple of light nails through them so they can't slide around on each other. Apply clamping pressure with weights like concrete blocks placed atop the blanks. Now stay away until the glue has set good and hard.

Now give the blade a final trimming and streamline the edges where required. (If your rudder, daggerboard, leeboard or centerboard vibrates in use, streamline the edges some more. That almost always cures the ailment.)

SINK WEIGHT...

I called this the "counterweight" in the drawing but "sink weight" is a better term.

The sink weight should be slightly heavier than the buoyancy of the immersed blade. Wood is about half as dense as water, and lead is about 11 times denser than water. It works out that the area of the lead weight should be about 1/16th the area of the immersed blade, or maybe 7 percent of the area to give a slight negative buoyancy. For example, a blade that is 10 inches by 15 inches immersed is 150 square inches. The lead weight could be 150 x .07 = 10.5 square inches, which would be a square 3.24 inches per side. Cut a hole in the blade for the lead to the proper size, preferably toward the tip and toward the trailing edge. Bevel the hole's edges so the lead will lock in place by forming flanges around the blade. Also place some rustproof nails or screws around the interior of the hole to further lock the lead in place. Clamp the blade to a flat metal plate and place it level on the floor.

To figure the weight of the lead required, multiply the area in inches by the thickness in inches and again by .4. In the example, if the example blade is 3/4" thick, the weight of the lead required is 10.5 x .7 x .4 = 3.15 pounds.

To melt the lead, I use a propane camp stove. I place it right next to the job so I woun't have to tote molten lead around the shop. For a crucible I use a coffee can with a 1/2" pour hole drilled about 3" above the bottom of the can, with a long metal handle bolted to the side of the can. The crucible goes on the stove with enough lead wheel weights inside sufficient for the pour.

Begin the pour as soon as the lead is molten. (The steel clamps on the wheel weights will float to the top and not pass through the pour hole.) Take your time and be very careful with the pour, but it must be done all at once. Overfill the hole in the rudder blade somewhat to allow for shrinkage on cooling. Shut off the stove and walk away from the job for a few hours. Lead stays very hot long after it has solidified.

If the weight gets loose in the blade due to shrinkage, you can tighten it by placing the weight over an anvil and hitting the lead with a hammer. That squeezes the center and expands the perimeter.

Now contemplate what it's like to pour a thousand pound keel!

RUDDER STOCK...

Laminate this exactly as you did the rudder blade. You need to add the downstop and it's amazing to me how sturdy this part needs to be. A block of hard rubber or phenolic plastic bolted in place might be best.

TILLER/HOIST LANYARD...

Don't make the tiller too short! Make it too long and shorten it later if needed. The tiller should fold neatly along the back edge of the rudder for storage.

Use light braided line, about 3/16" for the lanyard. Tie it to a small hole in the rudder's trailing edge. The hole needs to be located about where the raised rudder meets the aft end of the tiller. Then pass the lanyard through a hole in the back corner of the tiller, then forward to a small cleat on the top of the tiller. Pass the lanyard through a small hole in the base of the cleat and tie and loop for your fingers. To raise the rudder, yank on the lanyard and belay it around the little cleat. To lower the rudder, uncleat the lanyard and let the blade drop kerplunk against the stop.

SHEET FAIRLEAD...

This works very well on smaller sails that don't require multipart main sheets. Screw a fairlead solidly to the tiller's top face. Place the fairlead right above the rudder hinges so the sheet loads won't affect steering. Run the sail's sheet through the fairlead and forward along the tiller. You can secure the sheet merely by wrapping it a couple of times around the tiller's grip under your steering hand. Then you can steer and hold the sheet with the same hand. To release the sheet in a puff you need only slacken your grip without letting go of the tiller. You can also belay the sheet around the rudder lanyard cleat if you are feeling lucky.

HINGES...

I haven't figured out hinges yet. I think the best ones are welded up from stainless steel, but I'm working towards building boats totally from lumberyard stuff. Stevenson Projects used barrel bolt locks for hinges. Payson used eyebolts and rods. Dick Scobbie used door hinges with big cotter pins for pivots. Seeing those, I tried some door hinges on a dink rudder and was quite satisfied, especially since they came from the scrap bin. Most door hinges won't mount as simply as real boat fittings - check out the angles they swing through and do some head scratching.

One thing I'm sure of: Don't rely on gravity to keep your rudder on your transom. In a knockdown the rudder may unship and leave you with a very wet boat and no rudder. Also, with the sheet fairlead on the tiller as I've shown it, the sheet can produce a large upward force on the assembly in strong winds and lift the whole thing out of conventional fittings. Both of these things have happened to me. Now I secure conventional fittings against knockdowns and sheet loads by drilling as small hole in one pintle below the gudgeon and putting a cotter pin through the hole.

THE CARY HINGE...

I wrote the above a few years ago. But very recently I got letter from Ted Cary in Florida. He has a way of making effective rudder hinges from scrap seatbelts.

Here is his description:

"Thought you might be interested in my solution to the rudder pintle problem. My first experience trying to hit two gudgeons with the pintles in a big chop, while hanging over the transom, disqualified that system for me. I came up with a simple track and slide system, then epoxied up the slide and rudder stock around pieces of connecting webbing strap. The stap flexes when you steer. You can bend a seat belt a lot of times before it breaks, and nylon doesn't corrode in salt water. I found that you must align the strap longitudinally across the direction of the flex, and you must not allow the epoxy to harden on the strap where it has to flex. But the ends of the strap have to be well saturated to hold the slide and the rudderstock halves together. The most successful way I've used to avoid glue where I don't want it is to get the parts all glued up and assembled with clamps, keeping the glue off the flex line as much as possible. Then use a syringe or squirt bottle to saturate the flex line with vinegar, working it through the fibers, before the glue starts to set. The acetic acid neutralizes the amines in the epoxy hardener, so it won't polymerize. The clamped parts won't allow the vinegar to reach the glue on the strapping between them, so it goes off where you want it to."

"Dropping the triangular section slide down the transom track installs the rudder in a fraction of a second.This hinge rig has been working great on several dinks for over 4 years now."

Well, I must try Ted's system sometime. I think model airplane guys have been using flexing plastic hinges for a long time. My only comment might be that I would also lock the slide it to prevent it from unshipping in a knockdown.

Jonsboat

JONSBOAT, POWER SKIFF, 16' X 5', 200 POUNDS EMPTY

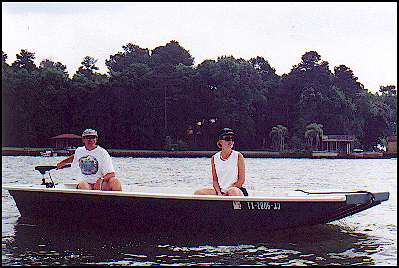

Jonsboat is just a jonboat. But where I live that says a lot because most of the boats around here are jonboats and for a good reason. These things will float on dew if the motor is up. This one shows 640 pounds displacement with only 3" of draft. That should float the hull and a small motor and two men. The shape of the hull encourages fast speeds in smooth water and I'd say this one will plane with 10 hp at that weight, although "planing" is often in the eye of the beholder. I'd use a 9.9 hp motor on one of these myself to allow use on the many beautiful small lakes we have here that are wisely limited to 10 hp. The prototype was built by Greg Rinaca of Coldspring, Texas and his boat is shown above when first launched with a trolling motor. But here is another one finished about the same time by Chuck Leinweber of Harper, Texas:

In the photo of Chuck's boat you can see the wide open center that I prefer in my own personal boats. To keep the wide open boat structurally stiff I boxed in the bow, used a wide wale, and braced the aft corners.

I usually study the shapes of commercial welded aluminum jonboats. It's surprising to see the little touches the builders have worked into such a simple idea. I guess they make these things by the thousands and it is worth while to study the details. Anyway, Jonsboat is a plywood copy of a livery boat I saw turned upside down for the winter. What struck me about that hull was that its bottom was constant width from stem to stern even though the sides had flare and curvature. When I got home I figured out they did it and copied it. I don't know if it gives a superior shape in any way but the bottom of this boat is planked with two constant width sheets of plywood.

Greg Rinaca put a new 18 hp Nissan two cycle engine on his boat, Here is a photo of it:

The installation presented a few interesting thoughts. First I've been telling everyone to stick with 10 hp although it's well known that I'm a big chicken about these things. Greg reported no problems and a top speed of 26 mph. I think the Coast Guard would limit a hull like this to about 25 hp, the main factors being the length, width, flat bottom, and steering location. Second, if you look closely at the transom of Greg's boat you will see that he has built up the transom in the motor mount area about 2". When I designed Jonsboat I really didn't know much about motors except that there were short and long shaft motors. I thought the short ones needed 15" of transom depth and didn't really know about the long shafts. Jonsboat has a natural depth of about 17" so I left the transom on the drawing at 17" and did some hand waving in the drawing notes about scooping out or building up the transom to match the requirements of your motor.

I think the upshot of it all is that short shaft motors need 15" from the top of the mount to the bottom of the hull and long shaft motors need 20". There was a lot of discussion about where the "cavitation" plate, which is the small flat plate right above the propellor, should fall with respect to the hull. I asked some expert mechanics at a local boat dealer and they all swore on a stack of tech manuals that a high powered boat will not steer safely if the cavitation plate is below the bottom of the hull, the correct location being about 1/2" to 1" above the bottom. But Greg had the Nissan manual and it said the correct position is about 1" BELOW the bottom. Kilburn Adams has a new Yamaha and its manual says the same thing. So I guess small motors are different from big ones in that respect.

But it seems to be not all that critical, at least for the small motors. Greg ran his Jonsboat with the 18 hp Nissan with the original 17" transom for a while and measured the top speed as 26 mph. Then he raised the transom over 2" and got the same top speed!

There is nothing to building Jonsboat. There five sheets of plywood and I'm suggesting 1/2" for the bottom and 1/4" for everything else. It's all stuck together with glue and nails using no lofting or jigs. I always suggest glassing the chines for abrasion resistance but I've never glassed more than that on my own boats and haven't regretted it. The cost, mess, and added labor of glassing the hull that is out of the water is enormous. My pocketbook and patience won't stand it. Glassing the chines and bottom is a bit different because it won't show and fussy finishing is not required.

Plans for Jonsboat are $25.

Prototype News

Some of you may know that in addition to the one buck catalog which now contains 20 "done" boats, I offer another catalog of 20 unbuilt prototypes. The buck catalog has on its last page a list and brief description of the boats currently in the Catalog of Prototypes. That catalog also contains some articles that I wrote for Messing About In Boats and Boatbuilder magazines. The Catalog of Prototypes costs $3. The both together amount to 50 pages for $4, an offer you may have seen in Woodenboat ads. Payment must be in US funds. The banks here won't accept anything else. (I've got a little stash of foreign currency that I can admire but not spend.) I'm way too small for credit cards.

We have a Picara finished by Ken Giles, past Mayfly16 master, and into its trials. The hull was built by Vincent Lavender in Massachusetts. There have been other Picaras finished in the past but I never got a sailing report for them...

And the Vole in New York is Garth Battista's of www.breakawaybooks.com, printer of my book and Max's old outboard book and many other fine sports books. Beautiful job! Garth is using a small lug rig for sail, not the sharpie sprit sail shown on the plans, so I will continue to carry the design as a prototype boat. But he has used it extensively on his Bahamas trip towed behind his Cormorant. Sort of like having a compact car towed behind an RV.

And a Deansbox seen in Texas:

Another prototype Twister is well along:

A brave soul has started a Robbsboat. He has a builder's blog at http://tomsrobbsboat.blogspot.com. (OOPS! He found a mistake in the side bevels of bulkhead5, says 20 degrees but should be 10 degrees.) This boat has been sailed and is being tested. He has found the sail area a bit much for his area and is putting in serious reef points.

AN INDEX OF PAST ISSUES

THE WAY BACK ISSUES RETURN!

MANY THANKS TO CANADIAN READER GAETAN JETTE WHO NOT ONLY SAVED THEM FROM THE 1997 BEGINNING BUT ALSO PUT TOGETHER AN EXCELLENT INDEX PAGE TO SORT THEM OUT....

THE WAY BACK ISSUES

1nov17, Water Ballast Details, Piccup Pram

15nov17, Scram Pram Capsize, Harmonica

1dec17, Sail Area Math, Ladybug

15dec17, Cartopping, Sportdory

1jan18, Trailering, Normsboat

15jan18, AF3 Capsize Test, Robote

1feb18, Bulkhead Bevels, Toto

15feb18, Sail Rig Spars, IMB

1mar18, Sail Rig Trim 1, AF4Breve

15mar18, Sail Rig Trim 2, Harmonica

1apr18, Two Totos, River Runner

15apr18, Capsize Lessons, Mayfly16

1may18, Scarfing Lumber, Blobster

15may18, Rigging Sharpie Sprit Sails, Laguna

1jun18, Rigging Lug Sails, QT Skiff

15jun18, RendLake 2018, Mixer

1jul18, Horse Power, Vireo14

15jul18, Motors per the Coast Guard, Vamp

1aug18, Propeller Pitch, Oracle

15aug18, Propeller Slip, Cormorant

1sep18, Measuring Prop Thrust, OliveOyl

Table of Contents